|

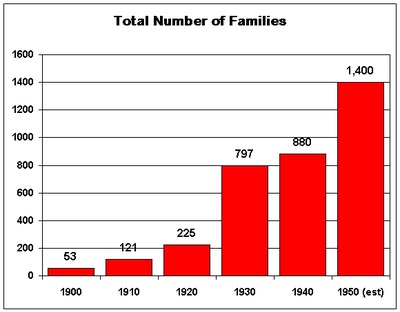

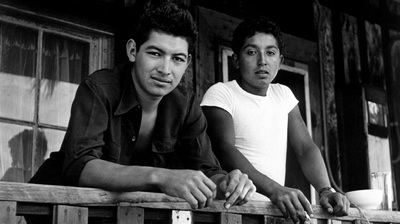

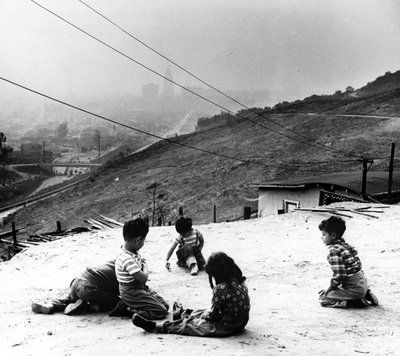

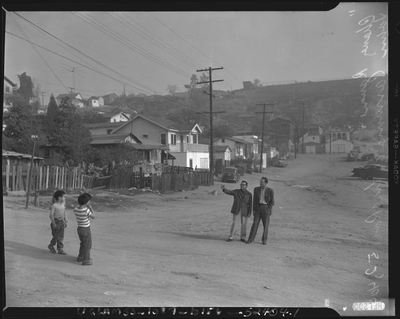

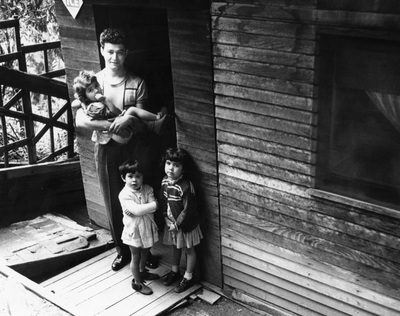

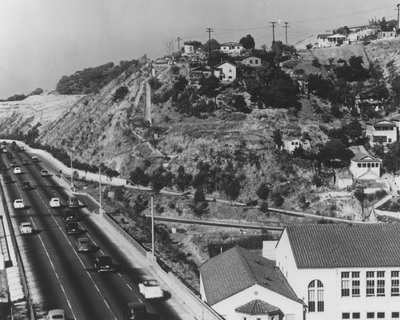

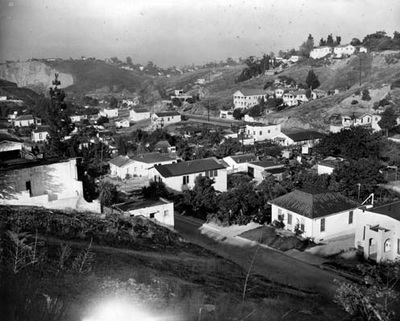

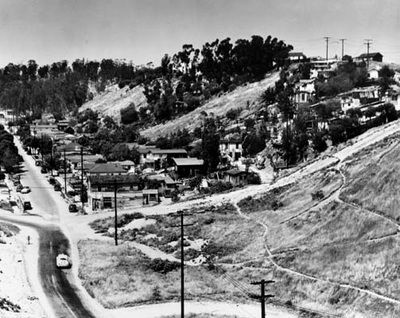

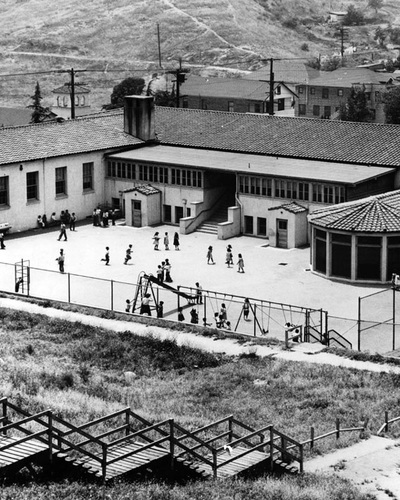

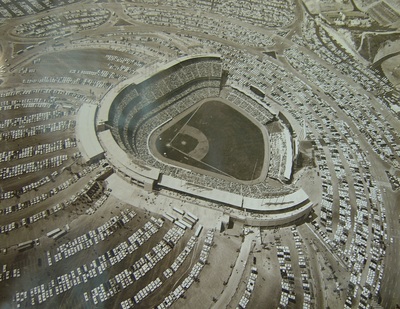

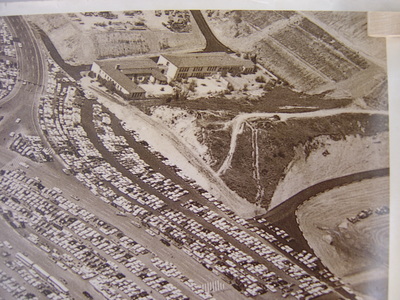

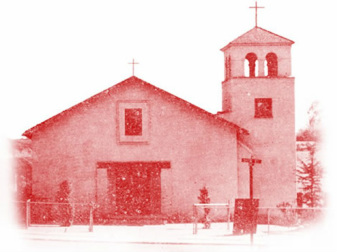

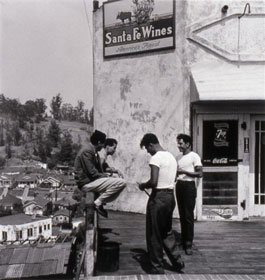

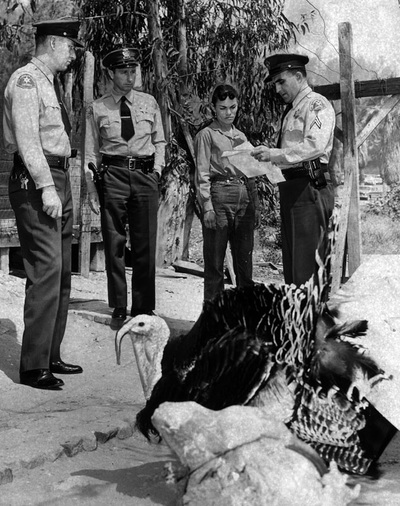

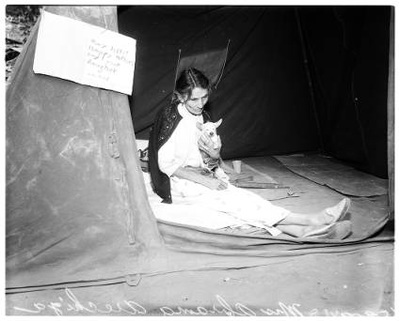

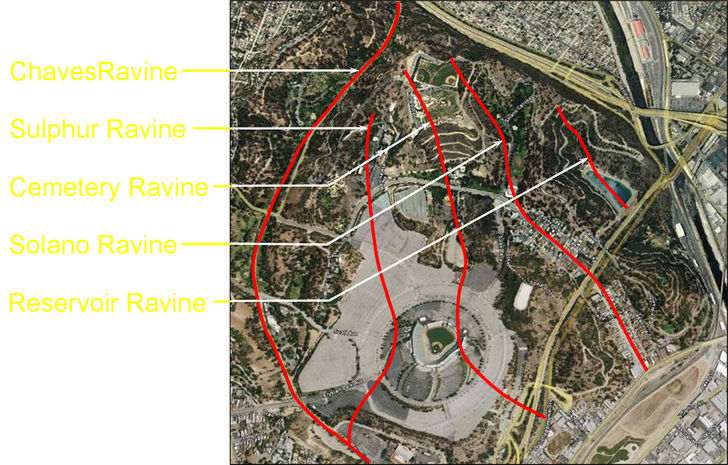

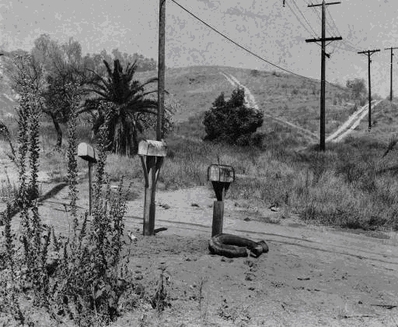

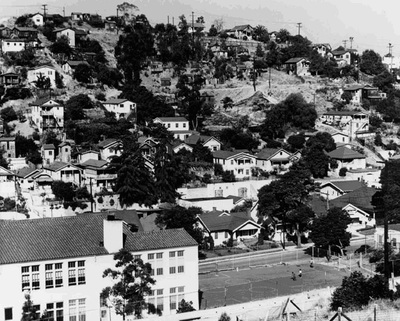

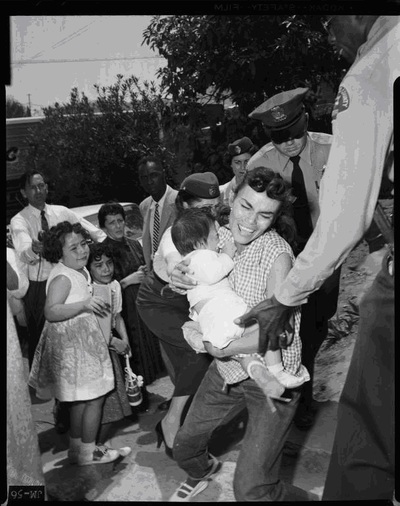

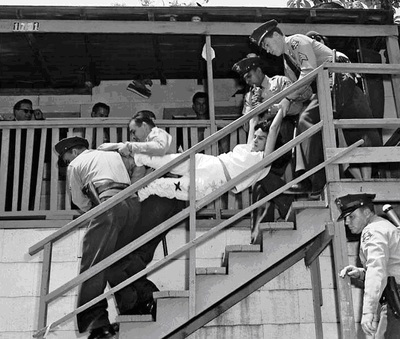

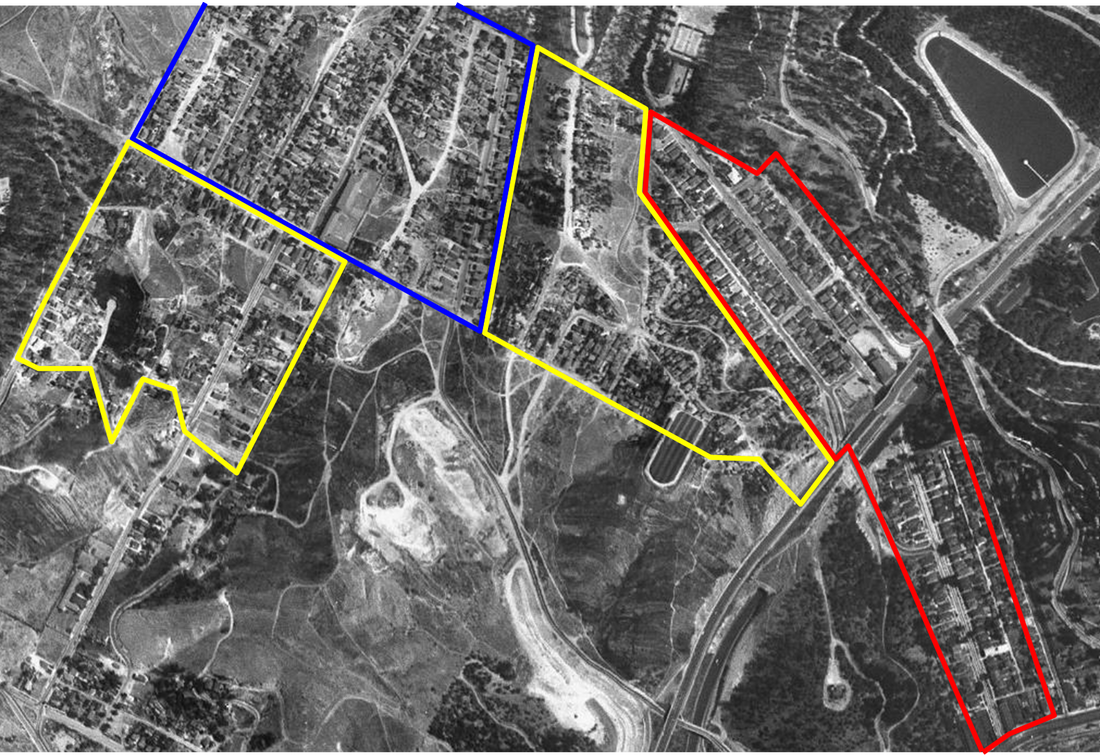

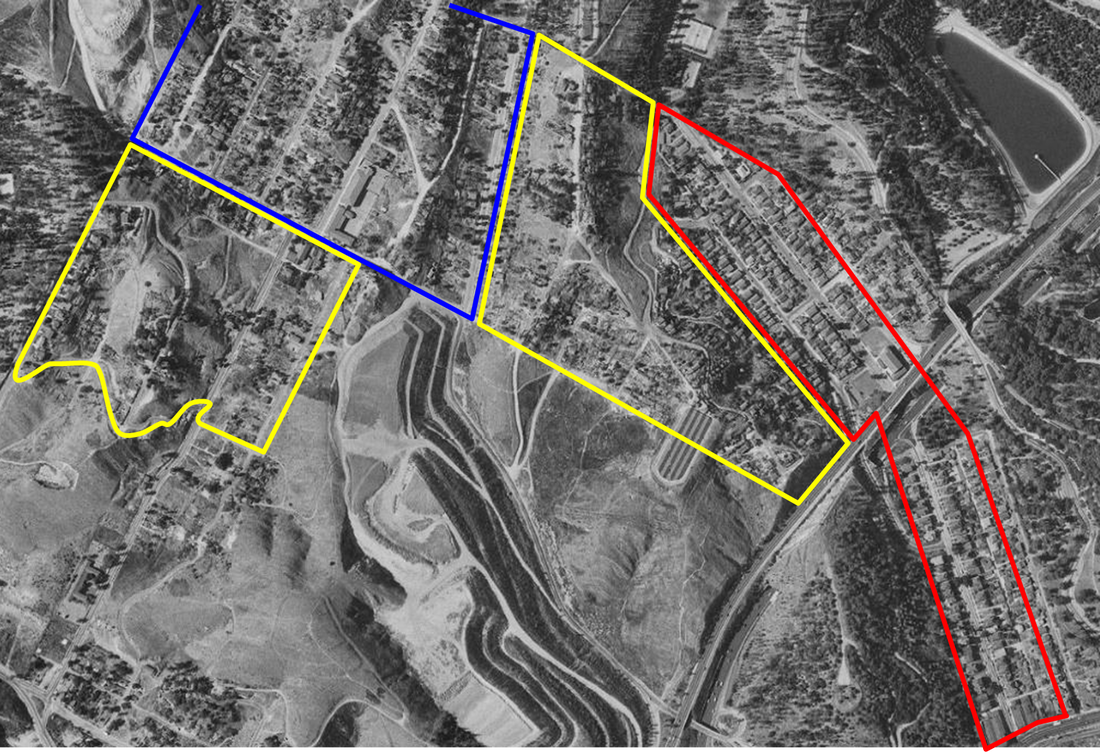

A handy, 'Lucky 13' check-list for Dodger fans to test their knowledge of what happened in Chavez Ravine so that Dodger Stadium could be built. We all know that all of us Dodger fans love our team — right? And no one can blame us for that — also right? But there are a few things we should probably stop and take a moment to consider, not about our Dodgers, but about what took place on the land on which Dodger Stadium is built. So it's not such a bad thing to take the opportunity to understand some history — right? Right! First, though, let's stipulate that when we say "Chavez Ravine" here, we're talking about the communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop that were home to thousands of people who were uprooted and evicted from their homes. Much of their land is now occupied by Dodger Stadium and its parking lots. 1. More than 1,100 families were evicted from their homes in la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop. It's true. There were about 415 families in la Loma, 575 in Palo Verde, and 110 in Bishop who were evicted from their homes, many of them forcibly. 2. A majority of the people who were evicted were of Hispanic origin, and most of the adults were born in México. Evidence from census records between 1900 and 1940 proves that the families that were evicted were about 73% Hispanic, and that most of the adults were from México. 3. In order to justify taking the land, the City had to characterize the entire Chavez Ravine area — the three communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop — as a 'slum' area. This blatant racism made it easier for the City to justify their condemning the Chavez Ravine communities and taking the land — by force is necessary. 4. Two elementary schools were destroyed. One was Palo Verde Elementary School and the other was Paducah Elementary School. The Palo Verde school was simply buried under tons of earth to build the pad for additional parking for Dodger Stadium. 5. El Santo Niño, a Catholic church that had existed since early in the 20th Century, was destroyed. The church of el Santo Niño was located in what is now the Dodger Stadium parking lot beyond center field. It was founded early in the 20th-Century; the earliest reference is a photograph taken in 1925. 6. A convent of Catholic nuns, the Sisters of the Society of Mary, fell victim to the evictions. The convent of the Sisters of the Society of Mary was located in a beautiful Victorian house at the intersection of Effie Street and Paducah Street in Palo Verde. 7. Chavez Ravine had its own stores. There were several stores in Chavez Ravine. Families did not have to go to downtown Los Angeles for much of their shopping. 8. Many residents of Chavez Ravine had gardens and raised their own food to help feed their families. Most of the homes in Chavez Ravine had small gardens. They grew a variety of things, including corn, beans, tomatoes, and chiles in order to help feed their families. 9. In addition to their gardens, other residents of Chavez Ravine raised animals, too. Among the animals raised by residents of Chavez Ravine were chickens, turkeys, goats, cows, and horses. 10. Many residents believed they were not given a fair price for their homes. Although the eviction notice of 1950 promised that residents were to receive a fair appraisal for their homes, the prices they were offered often did not match what the residents believed was fair, even if they were willing to leave and not be forcibly evicted. 11. The last evictions took place in 1959, just days before construction began on Dodger Stadium. One of the most heavily-documented evictions was that of the Aréchiga family in Palo Verde. The Aréchigas fought the eviction for nearly nine years before they were dragged out of their home by armed Sheriff's deputies. But they were not the only residents of Chavez Ravine who were displaced. Some of the survivors call themselves los Desterrados and they have a reunion each Summer in Chavez Ravine. The following images have no captions; the images speak for themselves. 12. How much of the land that was forcibly taken from more than 1,100 largely Hispanic families was actually used to build Dodger Stadlum? Was it really necessary to wipe the homes of 1,100 families off the face of Chavez Ravine to build Dodger Stadium? Look at the outlines of the communities. Isn't it possible that all of la Loma (the yellow outline on the right) and Palo Verde (the blue outline) could have been saved? Just who were these powerful people trying to get rid of, and why? Did it have to do with the color of their skin? Lucky 13. Finally, let's be clear: Dodger Stadium is not in Chavez Ravine. Dodger Stadium sits between Sulphur and Cemetery Ravines. There is an actual Chavez Ravine, but it is to the west of the stadium. Stadium Way today follows the original trail up Chavez Ravine to Frogtown. So, Dodger fans: by all means, enjoy Dodger baseball, and we wish the Dodgers all the best this season; but please, be aware that, when you are in the stadium, you are on sacred ground — it is the ground on which thousands of people once lived, worked, and played. An afterword. Chavez Ravine in media

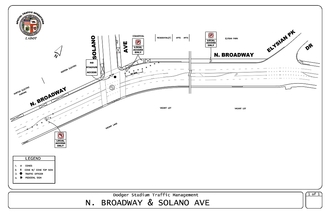

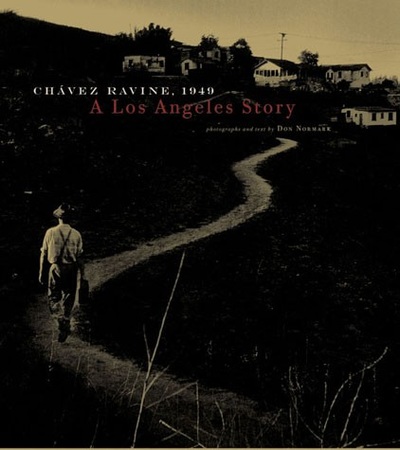

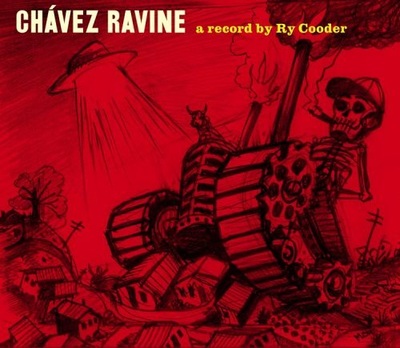

Gratefully, Chavez Ravine has not been completely forgotten. In addition to los Desterrados and others, these are some of the ways the heartbreaking story of the Chavez Ravine evictions has been portrayed in print (photographs and text), on the stage, in in music.  Why Solano Avenue and Casanova Street should never be used for access to Dodger Stadium Dodger Stadium traffic in Solano Canyon, especially on Solano Avenue, but also on Casanova Street — which has been renamed Academy Road north of the Pasadena Freeway (CA 110) — makes life for many Solano Canyon residents an unbearable Hell. We are used to thinking of driving in terms of miles-per-hour; but on game days in Solano Canyon, it's better to think of driving in terms of minutes-per-block — as in 20 minutes-per-block, or even more, according to testimony from more than one resident. Residents complained for years to the Dodgers, the City Council, the City Department of Transportation (DOT), and the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) with absolutely no relief. Finally, in 2013, a plan was put into place whereby no stadium traffic was allowed entry onto Solano Avenue from North Broadway. Note that the plan was designed by the City and bears the imprint of the Department of Transportation (DOT). The basis of the plan is simple:

It seemed like a good plan: residents could use Solano Avenue for access to their homes, but fans heading to Dodger Stadium could not; after all, the Downtown Gate is the preferred access to the stadium. Time for a (tiny) bit of history When Alfred Solano subdivided Solano Canyon in 1888, he imagined primary access to be from Solano Avenue, so he designed it 60' wide, including sidewalks, and with enough width that wagons could park along the street. Casanova Street, which was a minor street, was designed only 30' wide — wide enough for two wagons to pass, but with no space for 'parking'. Those two streets have the same dimensions today, even though Alfred, in his wisdom, petitioned the City in 1894 to widen Solano Avenue, a petition that was tabled at the time and ultimately never acted upon. Jump forward to the 21st-Century This is what Solano Avenue looks like on Dodger game days: Now let's imagine — Heaven forbid — that a man who lives on Solano Avenue has a heart attack. He thinks he can make it, but he calls 911. At the same time, a fire starts on the stove in the kitchen of a home on Casanova Street; that family, too, calls 911, then tries to put out the fire. Fire trucks and EMT ambulances rush to the locations, with lights flashing and sirens screaming. Cars — larger ones, like SUVs and some full-size cars — are about six feet wide, while many cars are more narrow. Fire trucks and ambulances, on the other hand, are a full eight feet wide or more. The paved surface of Solano Avenue is less than 40'. If two, six-foot-wide vehicles are parked on either side of the street, and they are each 18" from the curb, which is within the law, and two, six-foot-wide vehicles are driving on the street at the same time in opposite directions, then even though there is physically enough room for them all, most drivers do not feel comfortable driving very close to another vehicle. In practice, it has been proven that any object within about six feet of a vehicle makes most drivers uncomfortable. The point is that it would be extremely difficult — if not impossible — for an emergency vehicle, let alone several emergency vehicles, like a fire truck and an ambulance, to negotiate within the narrow confines of Solano Avenue, and literally impossible to negotiate the even-narrower Casanova Street. We can only hope for the best for that man who had the heart attack, and trust that the kitchen fire on Casanova Street was put out by the family, because in neither case would an emergency vehicle be able to provide a timely response to the emergency. NOTE: In the slide show below, each image is fully-captioned. Advance the slideshow manually using the arrows and hover your mouse momentarily over the large image to read its caption. Captions will not appear if the slide show is 'played'. Epilogue: The 2013 DOT traffic plan for Solano Avenue on Dodger game days is no longer being used; it was never rigorously enforced.

To watch the six-minute amateur video from which these images were taken, click here. For those who want a quick tour of what happened in Chavez Ravine The four neighborhoods that made up the Chavez Ravine communities are la Loma, Palo Verde, Bishop, and Solano Canyon; all but Solano Canyon are now gone, destroyed and leveled down to bare earth through eminent domain for a housing project that was proposed but died in its infancy and was never built. Much of the land is now occupied by Dodger Stadium and its parking lots. The streets that were contained within each of those communities are:

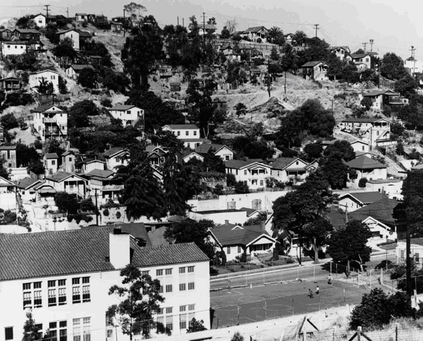

This is what Solano Canyon and la Loma looked like from above the Solano Avenue School circa 1930: The eviction notice for la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop is dated 24 July 1950. While some families sold their homes and relocated voluntarily, others did not. What is possibly the last eviction, that of the Arechiga family at 1771 Malvina Street, was captured on film: By the mid-1950s, when almost all of the evicted families had left, much of Chavez Ravine looked like this: Despite the evictions, the public housing project that was supposed to replace the ‘Latino slum’ in the hills, for which, the residents of Chavez Ravine were promised access to housing, was never built; instead, in 1962, this is what became of the Chavez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop: Don't it always seem to go ... with apologies to Joni Mitchell (Big Yellow Taxi, 1970) Note: 'A date to remember' is a new blog series that speaks to the importance of particular April 6, 2015 was Opening Day for the 2015 Major League Baseball season. For half of the teams in the league, that Monday meant a home game; for the other half, of course, it meant an away game. For the Los Angeles Dodgers, April 6th meant a home game. Go Blue, right? [That color, by the way, is the official Dodger Blue color hex #1e90ff, for those of you who care about such things.] Let's get right to the point: The purpose of any professional sports franchise is to make money. Is there anyone who doubts this? At Dodger Stadium, parking from 2013 to 2014 increased 50%, from $10 to $15, and from 2014 to 2015, it increased an additional 33%, from $15 to $20. I doubt most of us received wage or salary increases that matched the increases in parking prices. Ticket prices have increased as well, although not as much as the cost of parking. [Los Angeles Times, September 12, 2014] In the past — that is, until 2010 — tailgating was allowed inside the parking lots at Dodger Stadium. The practice, a long-time tradition remembered fondly by many loyal fans, was halted by Frank McCourt that year, citing rowdy behavior and public drunkenness as the primary drivers for the ban. As a result of the ban, tailgating moved from inside the parking lots of Dodger Stadium — a controlled space — to Elysian Park and the surrounding neighborhoods, including Echo Park and Solano Canyon. "In addition to being the start to the at-home season, [opening day] kicks off a season of There is a solution, however: Bring tailgating back to Dodger Stadium! Clicking on the link, above, takes you to a petition to the Dodgers new ownership and the McCourt Group to allow tailgating inside the parking lots of Dodger Stadium once more. Other MLB franchises allow it — notably Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and even Angel Stadium in Anaheim — so why not bring it back to Dodger Stadium? Not in my back yard! The Dodgers claim that the 'fan experience' — their words — is the thing that is most important to them. First, let's not forget the fundamental fact that The primary purpose of any professional sports franchise is to make money. So by sloughing off any responsibility for tailgating onto neighboring communities, the Dodger organization and the McCourt Group can remain pristine, their corporate hands unsullied by any potentially ugly fan behavior, while those same neighboring communities (and Elysian Park) bear the brunt of trash, public urination, and drunken behavior, all of which could be controlled much more easily if tailgating were permitted in the parking lots of Dodger Stadium. We wish the Dodgers well in their current season. Photo credits: Los Angeles Times, April 7, 2015

Warning: this is a quiz, and I'll also tell you that it's also a trick question. Q: When did baseball come to Chavez Ravine? Now, before you answer, I should warn you that by Chavez Ravine, I do not mean the actual ravine named Chavez Ravine; nor do I mean Dodger Stadium; nor to I mean the three communities — now gone — of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop that were collectively called Chavez Ravine. Think Elysian Park and its surroundings in the Stone Quarry Hills. So if you answered, "1962", you would be wrong. A: At least by 1912. OK, so you missed it; we all would have, except that I have a photograph that proves my answer. So who are these guys, anyway? Not the 'Boys in Blue', surely.

The back of the photograph says "Tufts-Lyon baseball team No. 2, Elysian Park, 1912". The third adult from the left is the author's grandfather, Teodoro Manuel Bouett. The boy is the team mascot and the man in the suit is the team's umpire (yes, teams brought their own umpire to games in those days). Tufts-Lyon was a major sporting goods store in Los Angeles from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. Many businesses had their own baseball teams and some of them were semi-pro. John Q. Tufts was a US Congressman from Iowa and a member of the Los Angeles City Council. An ancestor founded Tufts College, now Tufts University, near Boston. Tufts' business partner was F. M. Lyon. Together, they were strong supporters of baseball in early Los Angeles, and they even sponsored construction of a stadium in Lincoln Heights in the late 1880s. Another company baseball team was that of Dyas-Cline, which was another early-Los Angeles sporting goods store. Both the author's grandfather and father played for Dyas-Cline, and, at one time, they were on the team at the same time. We all play What If? games. What If? I had played my hunch on the lottery — those numbers won! What If? I had married so-and-so, who I knew in high school, and who is now a famous (and wealthy) movie star? You get the drift. What If? is a way to describe counterfactual history by exploring what did not happen in order better to understand what did happen. So, here's a What If? for the communities of Chavez Ravine — la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop:

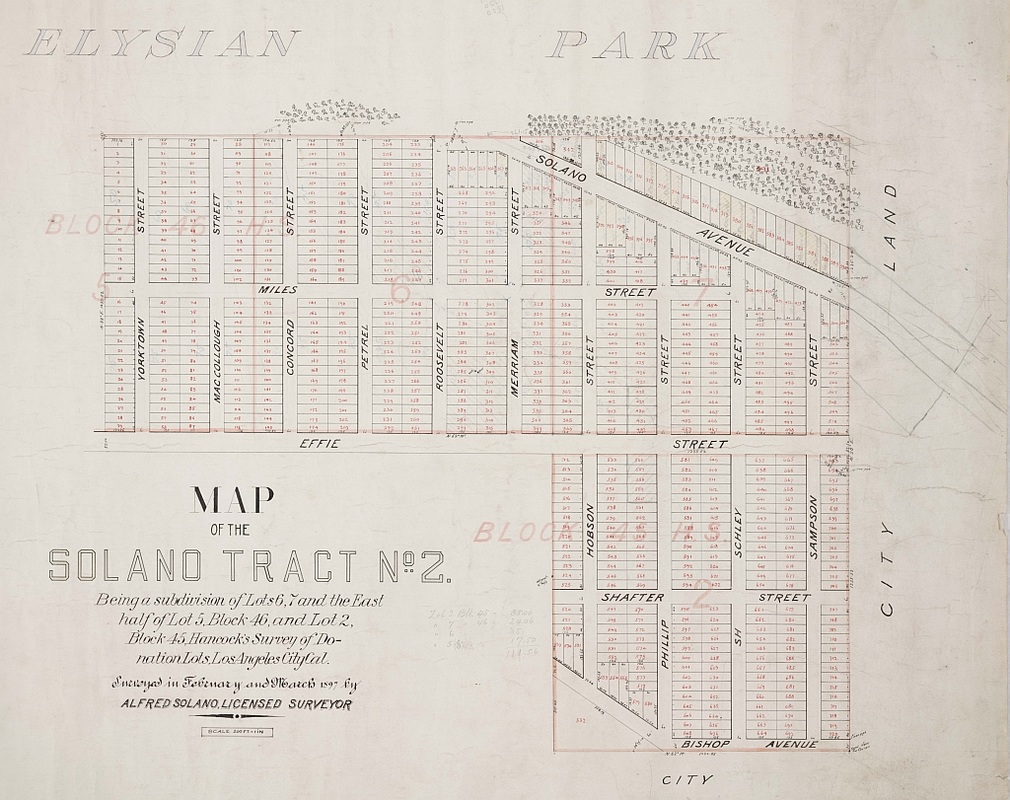

Here's what Alfred proposed to do with the land owned by the 'heirs of Francisco Solano' in 1897, apart from the already-developing Solano Canyon: This block, called Solano Tract No. 2, contains 720 numbered, 120' x 40' lots on 122½ acres. In terms of the Chavez Ravine communities, Solano Tract No. 2 covers all of la Loma (and more that was never built on), plus about half of Palo Verde, up to a point between Reposa and Gabriel Streets. About 80–90 lots in Palo Verde would not have been covered by this map, nor was any of Bishop. Notice Effie Street running horizontally through the center of the map and Solano Avenue near the top. The top of the original, 17-acre Solano Tract is just barely outlined at the right-hand side of the map.

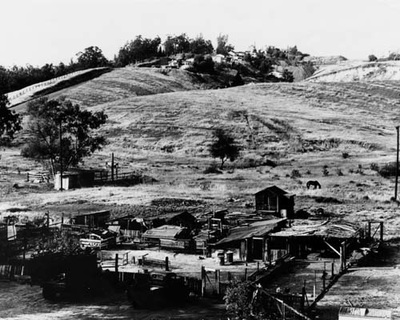

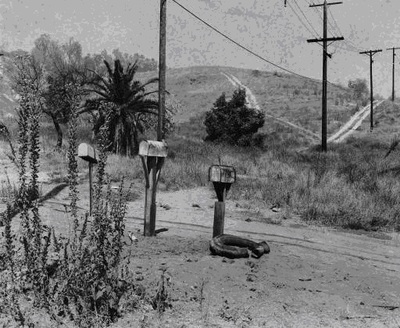

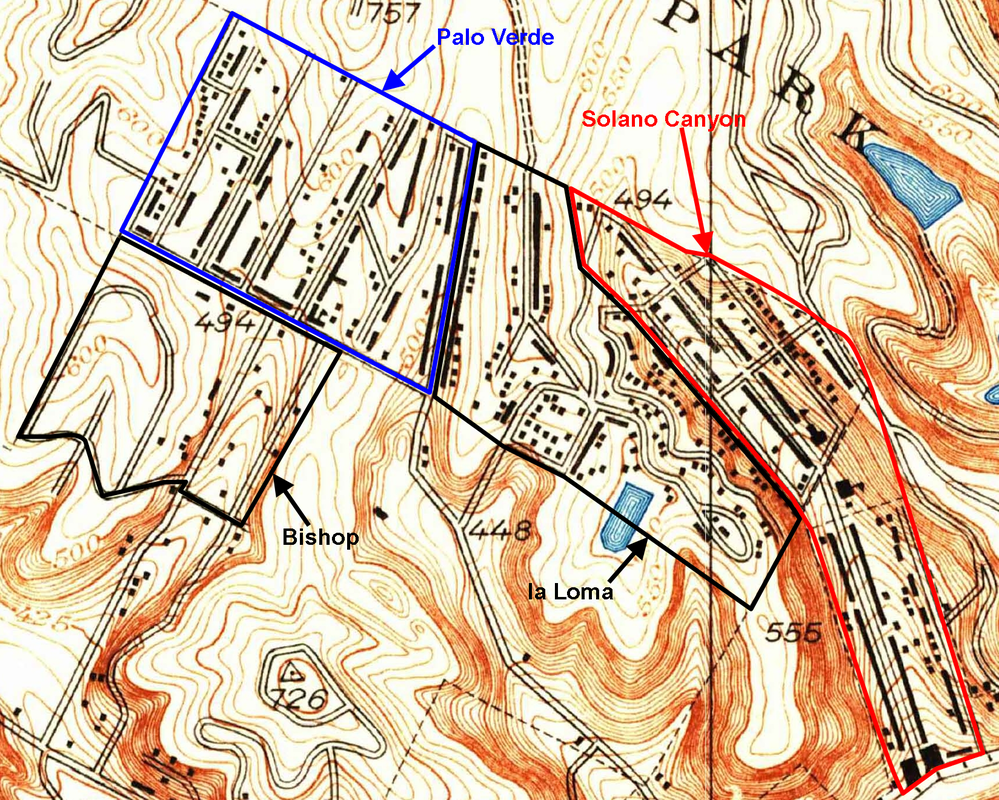

Alfred Solano was a surveyor and civil engineer, but he was also a businessman and philanthropist. He cared enough about the land that he preserved it after the deaths of his parents. He had obtained, on behalf of the Solano heirs, clear title to the land. When he sold property, the buyer knew he was being passed clear title. Now imagine that roughly 85% of the residents of la Loma and Palo Verde had clear title to their land and homes, and that their houses were built according to the building codes in effect at the time. Is it likely, then, that the so-called slum communities of la Loma and Palo Verde with their undesirable immigrant residents living in shacks would have been the target of a proposed low-income housing development? I think not. And if the land had not come into the possession of the City through eminent domain, would they have thought to locate a Major League Baseball franchise there? I think not ... An afterword: From entries in Alfred Solano's diaries, it is clear that the terrain — the steepness of the loma — is what precluded the original Solano Tract No. 2 subdivision from coming to fruition. But what if that had not frustrated Alfred's plan? What If? ... Part 3: Where, exactly, were the Chavez Ravine communities? These has always existed some confusion about where, exactly, the Chavez Ravine communities were located. There is no such confusion about Solano Canyon, since that community was rigorously surveyed and mapped by Alfredo Solano, son of Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova. Alfred, as he was known, was at various times Assistant County Surveyor and County Surveyor for Los Angeles County, and City Surveyor for the City of Los Angeles. The boundaries of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, however, known collectively as Chavez Ravine, were less well-defined. On the following map, those boundaries, plus that of Solano Canyon, are outlined. These boundaries admittedly involve a certain amount of intuition, and are not intended to be absolute; rather, they are intended to give the reader a certain sense of the relative locations of the communities. Note that the USGS quadrangle, of which, this map is a portion, shows the locations of the houses that existed at the time. Single black squares represent individual houses; solid black lines indicate houses closely-spaced. The geographic transition from Solano Canyon to la Loma was gradual and quite natural. The houses on both sides of Amador Street are clearly in Solano Canyon; but from there, the loma rose abruptly, and any houses built beyond those on Amador Street were a part of la Loma. Streets in Solano Canyon are Solano Avenue, Casanova Street, Amador Street, Jarvis Street, Bouett Street, and Brooks Avenue to its intersection with Bouett Street, all of which exist today. Streets in la Loma were Brooks Avenue from its intersection with Bouett Street to Effie Street, Phoenix Street, Spruce Street, Agua Pura Drive, Yolo Drive, Pine Street, and Effie Street from Bishop's Road to Yuba Street (which was also its intersection with Figueroa Street). It is likely that all of the houses on Bishop's Road between Effie Street and Park Row were considered a part of Palo Verde. A portion of Brooks Avenue, much of Spruce Street, and a portion of Agua Pura Drive still exist. With a bit of imagination, it is possible to intuit where Phoenix Street, which was never a fully-designated or paved street, existed. Streets in Palo Verde all ran from Effie Street to Park Row, with house numbers ranging from 1700 to about 1875. They were Bishop's Road, Davis Street, Curtis Street, Palo Verde Street (later renamed Paducah Street), Reposa Street, Gabriel Avenue, Malvina Avenue, and Boylston Street. A portion of Bishop's Road exists today in the parking lot of Dodger Stadium, and there still is a short block of Malvina Street alongside the parking lot of the Los Angeles Police Academy, whose address at one time was Boylston Street. The address of the Elysian Park Recreation Center, now the Elysian Park Adaptive Center and where the Los Angeles Theater Academy (LATA) is located today had, at one time, a Bishop's Road address. Streets in Bishop ran southwest from Effie Street, with house numbers below 1700. They were Davis Street, Paducah Street, Shoreland Drive, Home Place, Boylston Street, and Garibaldi Street. There is a short bit of Boylston Street that exists today; it is high on a loma, with a spectacular view of the fireworks displays that take place on certain Friday evenings following baseball games at Dodger Stadium. Before the evictions, the view would have been of the homes of their neighbors who lived with them in Bishop. The following map is a 1948 aerial photograph, in which individual houses may be seen — hundreds of them, in all the communities. This photograph was taken just two years before the evictions began. The four communities are outlined as before, except that la Loma and Bishop are outlined in yellow for clarity. Finally, take a look at nearly the same aerial photograph, this one taken in 1952 — two years after the evictions began. There's not much that may be said about the destruction that had taken place in just two years, so see for yourself ... While a few scattered houses remain in Chavez Ravine, mostly in Palo Verde, the end had already been determined and was clear. Thus, less than seven years after this heart-rending photograph was taken, out of a well-developed, vigorous, and tightly-knit community of about 1,400 families, all of the houses in la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop — nearly 1,100 in number — had been leveled. Solano Canyon, which will celebrate its 150th anniversary in 2016, was the lone survivor.

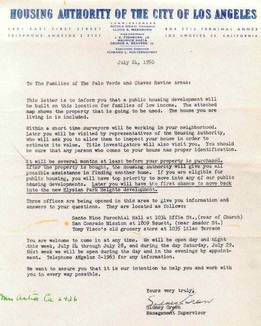

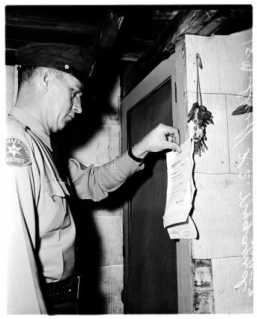

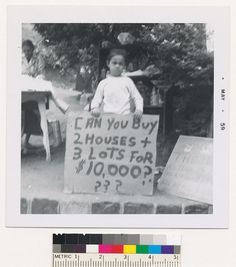

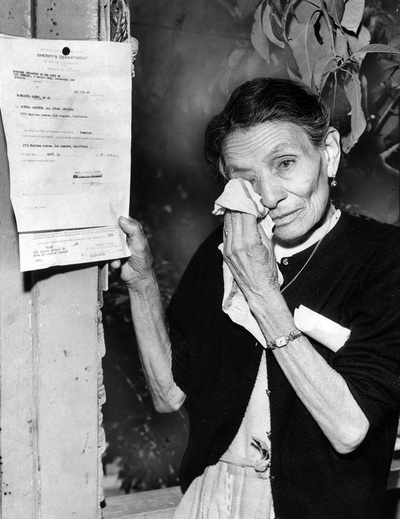

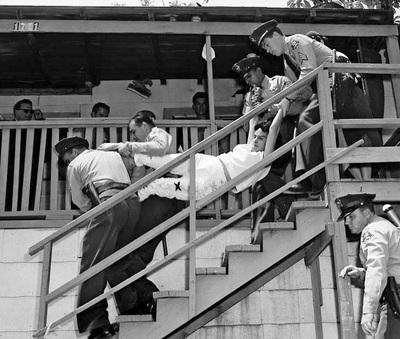

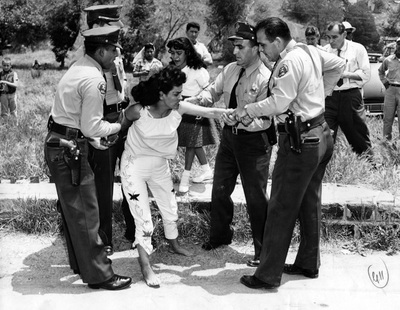

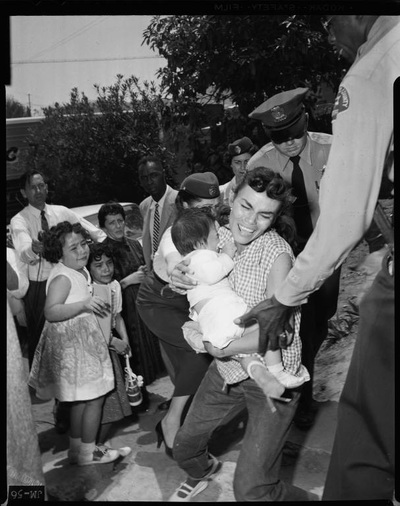

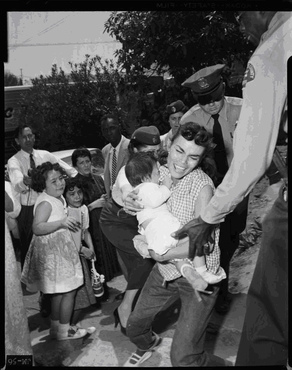

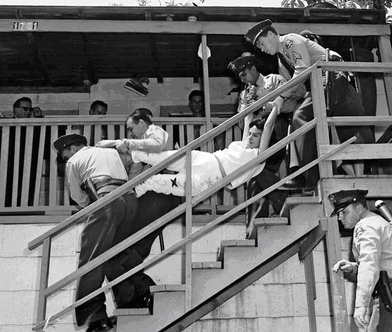

Source: From the personal collection of someone who was a witness to the evictions as a child. Source: From the personal collection of someone who was a witness to the evictions as a child. Part 2: The destruction of a way of life The wholesale destruction of the way of life of multiple, entire communities is one thing, and that is bad enough; but the forcible eviction and physical destruction of their homes, often before their very eyes and the eyes of their family and children, is another thing altogether, and is worthy of our disgust. At left is a copy of the eviction notice that was presented to the residents of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop by officers of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department beginning July 26, 1950. Where possible, it was handed directly to the residents by the officers; if there were no one at home, it was affixed to the house where it would be seen when the residents returned. The eviction notice that residents received or found attached to their homes was merely the first salvo in a battle that some of the residents of Chavez Ravine thought they might have been able ultimately to win; but it was only the first of many such battles, and even though the most determined of them, perhaps exemplified by the family of Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga, who lived at 1771 Malvina Street in Palo Verde, fought this battle — and all the others as well — for nearly nine years, winning some while losing others, taken together it was a larger war that they simply had no chance of winning from the outset. So by their responding to the eviction notice by saying they would not move under any circumstance, they set themselves on a path that was at once both courageous and pathetic. They were doomed to lose, and lose they did, right down to the last eviction, of the Aréchigas, nearly ten years later, on May 9, 1959. But one step at a time ...  Source: USC Digital Library EXM-N-12539-001-02 Source: USC Digital Library EXM-N-12539-001-02 The eviction notice notified residents that a low-income public housing development was going to be built on their property. It stated explicitly that inspectors would assess the value of their homes fairly, which implied that they would be paid fair market value for their respective properties. The notice further offered them assistance in finding temporary housing while the public housing project was being built, and to give them the first opportunity to move into that housing. There is a legitimate argument to be made that, in the end, everything that was promised turned out to be untrue. Why did the promises made in the eviction notice of 1950 turn out to be largely untrue? That is a matter of speculation, and there has been no limit to that speculation. Much academic research has been conducted in an attempt to document the timeline and posit the reasons for what happened. Was it simply the end result of a rapidly-shifting public opinion that swayed the intentions of the City Council? Was it the rapidly-increasing fear of Communism and the label of 'creeping Socialism', exemplified by construction of low-income public housing, that was fed by the political hysteria of the early 1950s? Had someone thought, 'Let's not build low-income housing for all these slum-dwelling minorities who live in shacks in the hills'? Did some forward-thinker say, "Look, if we condemn these properties and clear the land, we can sell it to Walter O'Malley for $1, build a new baseball stadium, and bring the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles"? In fact, irrespective of why 1,100 families were displaced, the land was sold to Walter O'Malley for $1, a new baseball stadium was built on the land, and the Brooklyn Dodgers were brought to Los Angeles. The last family was evicted from Chavez Ravine on May 9, 1959 and ground was broken for construction of Dodger Stadium 141 days later, on September 17, 1959. All of these scenarios, and more, have been argued and discussed endlessly since the 1950s. For all we know for certain, the truth may lie in an amalgam of some, or all, of them. It is not the purpose of this blog to determine which of the theories of malintent or conspiracy is true, if any; rather, this is intended as a chronicle of the suffering and horror that was experienced by those Chavez Ravine residents who were determined to retain and preserve their property. Next: Part 3: Where, exactly, were the three Chavez Ravine communities? |

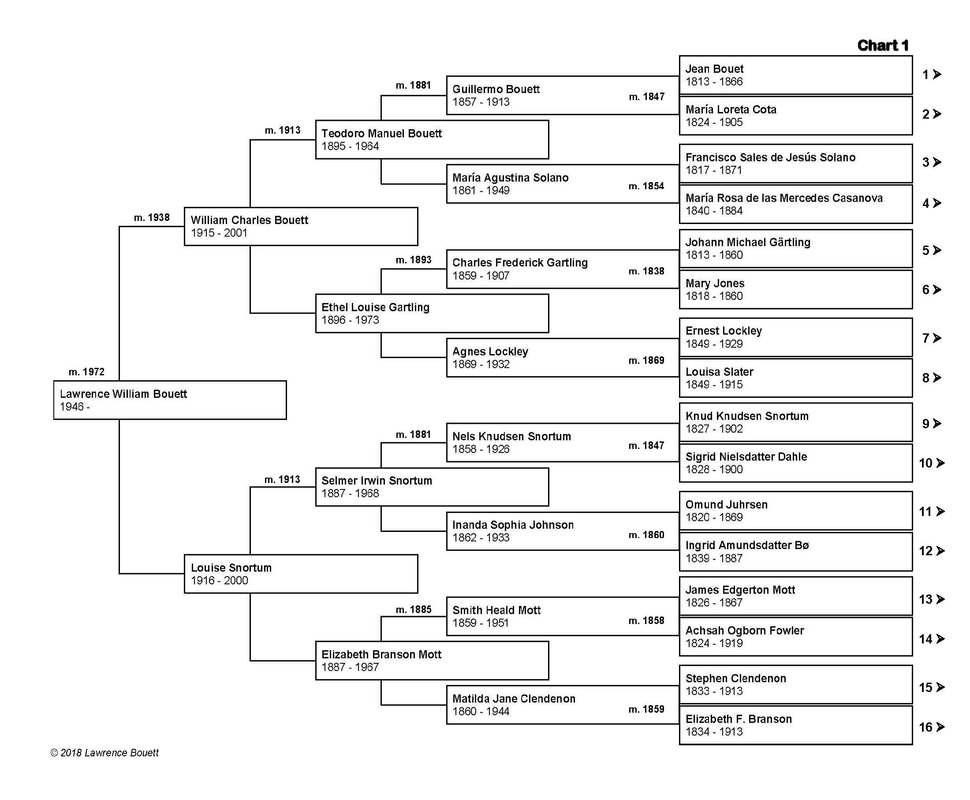

About the AuthorLawrence

Bouett is a retired research scientist and registered professional

engineer who now conducts historical and genealogical research

full-time. A ninth-generation Californian, he is particularly interested in the displacement of the nearly 1,100 families that lived in the Chavez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop to make way, ultimately, for the construction of Dodger Stadium. His ancestors arrived in California with Portolá in 1769 and came to Los Angeles with the founders on September 4, 1781. CategoriesArchives

January 2018

|

Follow us!

What our friends are saying

"Thank you for such an informative site which highlights the plight of those relocated from Chavez Ravine. My stepfather was a happy child growing up in the Palo Verde area. He had many stories about living in the area and working at the [Ayala] store."

"Wow that is awesome thank you"

"Dodger Stadium will always be a monument to the displacement of three entire communities"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed