The Real Story of Chavez Ravine

1: The Growth of a Vibrant Cluster of Communities

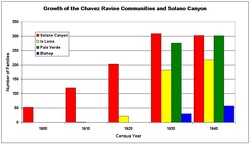

Source: NARA, US Census, 1900–1940

Source: NARA, US Census, 1900–1940

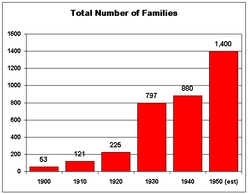

According to United States population census data, by 1940 there were 577 heads-of-household in the Chavez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, plus an additional 303 heads-of-household in Solano Canyon, for a total of 880. Census data are not available after 1940, but it is reasonable to assume that the four communities continued to grow, at times rapidly, at least until the eviction notice of 1950 was issued, when it was estimated that there were nearly 1,100 families living in Chavez Ravine. We can also assume that many, if not most, of the heads-of-household represented families rather than individuals living alone.

From its modest beginning in 1866, when Francisco Solano moved his family from Sonoratown to what was eventually to become Solano Canyon, by 1900 Solano Canyon comprised just 53 households. At that time, however, there were no households at all yet in what were to become the Chavez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop. As late as 1920, Solano Canyon accounted for 90% of the 225 households in the area, while all of the remainder — a mere 22 households — were located in la Loma. By 1930, Solano Canyon accounted only for slightly less than 40% of all families; by 1940, it was down to 34%, and by 1950 — which marked the beginning of the end for Chavez Ravine — Solano Canyon accounted for a mere 20% of households. One thing to notice from this chart is the very large jump in growth during the 1920s, as Palo Verde became populated and la Loma continued to grow. The 1940s marked another period of substantial growth, which is clear from the chart. It is perhaps fair to say that, while Solano Canyon may have been the 'seed community' for the development of the three Chavez Ravine communities, it was, ironically, the only one of the four communities that survived the disastrous purge of the 1950s.

From its modest beginning in 1866, when Francisco Solano moved his family from Sonoratown to what was eventually to become Solano Canyon, by 1900 Solano Canyon comprised just 53 households. At that time, however, there were no households at all yet in what were to become the Chavez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop. As late as 1920, Solano Canyon accounted for 90% of the 225 households in the area, while all of the remainder — a mere 22 households — were located in la Loma. By 1930, Solano Canyon accounted only for slightly less than 40% of all families; by 1940, it was down to 34%, and by 1950 — which marked the beginning of the end for Chavez Ravine — Solano Canyon accounted for a mere 20% of households. One thing to notice from this chart is the very large jump in growth during the 1920s, as Palo Verde became populated and la Loma continued to grow. The 1940s marked another period of substantial growth, which is clear from the chart. It is perhaps fair to say that, while Solano Canyon may have been the 'seed community' for the development of the three Chavez Ravine communities, it was, ironically, the only one of the four communities that survived the disastrous purge of the 1950s.

Source: NARA, US Census, 1900–1940

Source: NARA, US Census, 1900–1940

Another way of looking at the data is to break down the change in the number of households by community over time. Look at the steady growth of the number of households in Solano Canyon until the 1930s, when the population leveled off because all of the available house lots had been sold, built on, and were occupied by families. Meanwhile, the number of households in la Loma multiplied eightfold, from those 22 in 1920 to 182 by 1930, and with a further increase to 218 by 1940.

The growth of Palo Verde was even more dramatic. There were no homes at all in Palo Verde in 1920, but by 1930, there were 276, which was considerably more than in all of la Loma, which was limited by space, and nearly as many as the 309 in Solano Canyon itself, which was also space-limited. Bishop, meanwhile, came into being as a community during the 1930s, and by 1940, contained 57 homes.

The populations of the three Chavez Ravine communities — la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop — continued to grow during the 1940s, and, by 1950, was estimated at nearly 1,100 households. But, by then, the end was already at hand.

The growth of Palo Verde was even more dramatic. There were no homes at all in Palo Verde in 1920, but by 1930, there were 276, which was considerably more than in all of la Loma, which was limited by space, and nearly as many as the 309 in Solano Canyon itself, which was also space-limited. Bishop, meanwhile, came into being as a community during the 1930s, and by 1940, contained 57 homes.

The populations of the three Chavez Ravine communities — la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop — continued to grow during the 1940s, and, by 1950, was estimated at nearly 1,100 households. But, by then, the end was already at hand.

2: The Destruction of a Way of Life

Source: From the personal collection of someone who was a witness to the evictions as a child.

Source: From the personal collection of someone who was a witness to the evictions as a child.

The wholesale destruction of the way of life of multiple, entire communities is one thing, and that is bad enough; but the forcible eviction and physical destruction of their homes, often before their very eyes and the eyes of their families and children, is another thing altogether, and it is worthy of close examination as well as our disgust.

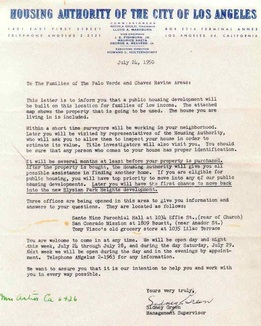

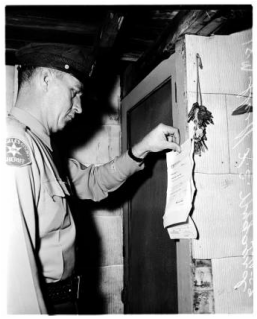

At left is a copy of the eviction notice that was presented to the residents of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop by officers of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department beginning July 26, 1950. Where possible, it was handed directly to the residents by the officers; if there were no one at home, it was affixed to the house where it would be seen when the residents returned.

The eviction notice that residents received or found attached to their homes was merely the first salvo in a battle that some of the residents of Chavez Ravine thought they might be able ultimately to win; but it was only the first of many such battles, and even though the most determined of them, perhaps exemplified by the family of Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga, who lived at 1771 Malvina Street in Palo Verde, fought this battle — and all the others who fought as well — for nearly nine years, winning some while losing others, taken together it was a larger war that they simply had no chance of winning from the outset. So by their responding to the eviction notice by saying they would not move under any circumstance, they set themselves on a path that was at once both courageous and pathetic. They were doomed to lose, and lose they did, right down to the last eviction, of the Aréchigas, nearly ten years later, on May 9, 1959.

But one step at a time ...

At left is a copy of the eviction notice that was presented to the residents of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop by officers of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department beginning July 26, 1950. Where possible, it was handed directly to the residents by the officers; if there were no one at home, it was affixed to the house where it would be seen when the residents returned.

The eviction notice that residents received or found attached to their homes was merely the first salvo in a battle that some of the residents of Chavez Ravine thought they might be able ultimately to win; but it was only the first of many such battles, and even though the most determined of them, perhaps exemplified by the family of Manuel and Abrana Aréchiga, who lived at 1771 Malvina Street in Palo Verde, fought this battle — and all the others who fought as well — for nearly nine years, winning some while losing others, taken together it was a larger war that they simply had no chance of winning from the outset. So by their responding to the eviction notice by saying they would not move under any circumstance, they set themselves on a path that was at once both courageous and pathetic. They were doomed to lose, and lose they did, right down to the last eviction, of the Aréchigas, nearly ten years later, on May 9, 1959.

But one step at a time ...

Source: USC Digital Library EXM-N-12539-001-02

Source: USC Digital Library EXM-N-12539-001-02

The eviction notice notified residents that a low-income public housing development was going to be built on their property. It stated explicitly that inspectors would assess the value of their homes fairly, which implied that they would be paid fair market value for their respective properties. The notice further offered them assistance in finding temporary housing while the public housing project was being built, and to give them the first opportunity to move into that housing. There is a legitimate argument to be made that, in the end, everything that was promised turned out to be untrue.

Why did the promises made in the eviction notice of 1950 turn out to be largely untrue? That is a matter of speculation, and there has been no limit to that speculation. Much academic research has been conducted in an attempt to document the timeline and posit the reasons for what happened. Was it simply the end result of a rapidly-shifting public opinion that swayed the original intentions of the City Council? Was it the rapidly-increasing fear of Communism and the label of 'creeping Socialism' that was exemplified by construction of low-income public housing, that was fed by the political hysteria of the early 1950s? Had someone thought, 'Let's not build low-income housing for all these slum-dwelling minorities who live in shacks in the hills'? Did some forward-thinker say, "Look, if we condemn these properties and clear the land, we can sell it to Walter O'Malley for $1, build a new baseball stadium, and bring the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles"? In fact, irrespective of why 1,100 families were displaced, the land was sold to Walter O'Malley for $1, a new baseball stadium was built on the land, and the Brooklyn Dodgers were brought to Los Angeles. The last family was evicted from Chavez Ravine on May 9, 1959 and ground was broken for construction of Dodger Stadium 141 days later, on September 17, 1959.

All of these scenarios, and more, have been argued and discussed endlessly since the 1950s. For all we know for certain, the truth may lie in an amalgam of some, or all, of them. It is not the purpose of this blog to determine which of the theories of malintent or conspiracy is true, if any; rather, this is intended as a chronicle of the suffering and horror that was experienced by those Chavez Ravine residents who were determined to retain and preserve their property.

Why did the promises made in the eviction notice of 1950 turn out to be largely untrue? That is a matter of speculation, and there has been no limit to that speculation. Much academic research has been conducted in an attempt to document the timeline and posit the reasons for what happened. Was it simply the end result of a rapidly-shifting public opinion that swayed the original intentions of the City Council? Was it the rapidly-increasing fear of Communism and the label of 'creeping Socialism' that was exemplified by construction of low-income public housing, that was fed by the political hysteria of the early 1950s? Had someone thought, 'Let's not build low-income housing for all these slum-dwelling minorities who live in shacks in the hills'? Did some forward-thinker say, "Look, if we condemn these properties and clear the land, we can sell it to Walter O'Malley for $1, build a new baseball stadium, and bring the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles"? In fact, irrespective of why 1,100 families were displaced, the land was sold to Walter O'Malley for $1, a new baseball stadium was built on the land, and the Brooklyn Dodgers were brought to Los Angeles. The last family was evicted from Chavez Ravine on May 9, 1959 and ground was broken for construction of Dodger Stadium 141 days later, on September 17, 1959.

All of these scenarios, and more, have been argued and discussed endlessly since the 1950s. For all we know for certain, the truth may lie in an amalgam of some, or all, of them. It is not the purpose of this blog to determine which of the theories of malintent or conspiracy is true, if any; rather, this is intended as a chronicle of the suffering and horror that was experienced by those Chavez Ravine residents who were determined to retain and preserve their property.

3: The Location of the Chavez Ravine Communities

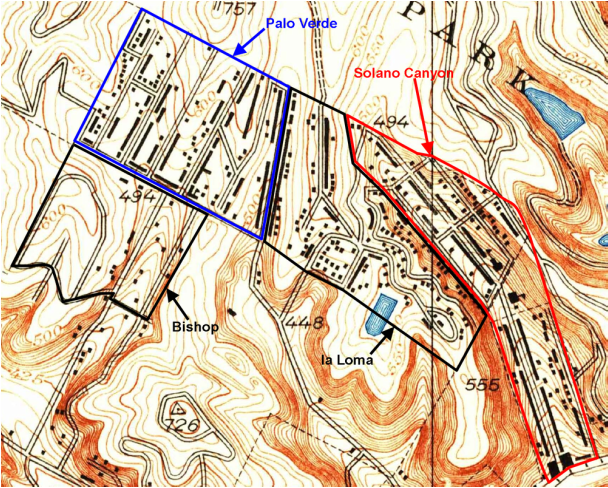

There has always existed some confusion about where, exactly, the Chavez Ravine communities were located. There is no such confusion about Solano Canyon, since that community was rigorously surveyed and mapped by Alfredo Solano, son of Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova, originally in 1866 and again in 1888. Alfred, as he was known, was at various times Assistant County Surveyor and County Surveyor for Los Angeles County, and City Surveyor for the City of Los Angeles.

The boundaries of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, however, known collectively as Chavez Ravine, were less well-defined. On the following map, those boundaries, plus that of Solano Canyon, are outlined. These boundaries admittedly involve a certain amount of intuition, and are not intended to be absolute; rather, they are intended to give the reader a certain sense of the relative locations of the four communities.

Note that the 1928 USGS quadrangle, of which, this map is a portion, shows the locations of the houses that existed at the time. Single black squares represent individual houses; solid black lines indicate houses that are closely-spaced.

The boundaries of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, however, known collectively as Chavez Ravine, were less well-defined. On the following map, those boundaries, plus that of Solano Canyon, are outlined. These boundaries admittedly involve a certain amount of intuition, and are not intended to be absolute; rather, they are intended to give the reader a certain sense of the relative locations of the four communities.

Note that the 1928 USGS quadrangle, of which, this map is a portion, shows the locations of the houses that existed at the time. Single black squares represent individual houses; solid black lines indicate houses that are closely-spaced.

The geographic transition from Solano Canyon to la Loma was gradual, continuous, and quite natural. The houses on both sides of Amador Street are clearly a part of Solano Canyon; but from there, the loma rose abruptly, and any houses built beyond those that faced Amador Street were a part of la Loma.

Streets in Solano Canyon are Solano Avenue, Casanova Street, Amador Street, Jarvis Street, Bouett Street, and Brooks Avenue to its intersection with Bouett Street, all of which exist today.

Streets in la Loma were Brooks Avenue from its intersection with Bouett Street to Effie Street, Phoenix Street, Spruce Street, Agua Pura Drive, Yolo Drive, Pine Street, and Effie Street from Bishop's Road to Yuba Street (which was also Yuba Street's intersection with Figueroa Street). It is likely that all of the houses on Bishop's Road between Effie Street and Park Row were considered a part of Palo Verde. A portion of Brooks Avenue, much of Spruce Street, and a portion of Agua Pura Drive still exist. With a bit of imagination, it is possible to intuit where Phoenix Street, which was never a fully-designated or paved street, existed.

Streets in Palo Verde all ran from Effie Street to Park Row, with house numbers ranging from 1700 to about 1875. They were Bishop's Road, Davis Street, Curtis Street, Palo Verde Street (later renamed Paducah Street), Reposa Street, Gabriel Avenue, Malvina Avenue, and Boylston Street. A portion of Bishop's Road exists today in the parking lot of Dodger Stadium, and there still is a short block of Malvina Street alongside the parking lot of the Los Angeles Police Academy, whose address at one time was on Boylston Street. The address of the Elysian Park Recreation Center, now the Elysian Park Adaptive Center and where the Los Angeles Theater Academy (LATA) is located today had, at one time, a Bishop's Road address.

Streets in Bishop ran southwest from Effie Street, with house numbers below 1700. They were Davis Street, Paducah Street, Shoreland Drive, Home Place, Boylston Street, and Garibaldi Street. There is a short bit of Boylston Street that exists today; it is high on a loma, with a spectacular view of the fireworks displays that take place on certain Friday evenings following baseball games at Dodger Stadium. Before the evictions, the view would have been of the homes of their neighbors who lived with them in Bishop. There is also a very short portion of Shoreland Drive that exists today off of Boylston Street.

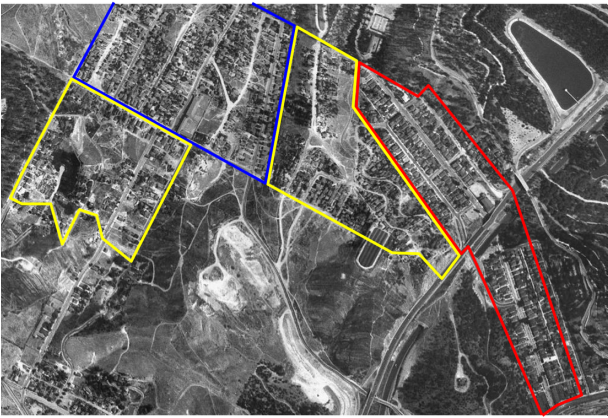

The following map is a 1948 aerial photograph, in which individual houses may be seen — hundreds of them, in all the communities. This photograph was taken just two years before the evictions began. The four communities are outlined as before, except that la Loma and Bishop are outlined in yellow for clarity.

Streets in Solano Canyon are Solano Avenue, Casanova Street, Amador Street, Jarvis Street, Bouett Street, and Brooks Avenue to its intersection with Bouett Street, all of which exist today.

Streets in la Loma were Brooks Avenue from its intersection with Bouett Street to Effie Street, Phoenix Street, Spruce Street, Agua Pura Drive, Yolo Drive, Pine Street, and Effie Street from Bishop's Road to Yuba Street (which was also Yuba Street's intersection with Figueroa Street). It is likely that all of the houses on Bishop's Road between Effie Street and Park Row were considered a part of Palo Verde. A portion of Brooks Avenue, much of Spruce Street, and a portion of Agua Pura Drive still exist. With a bit of imagination, it is possible to intuit where Phoenix Street, which was never a fully-designated or paved street, existed.

Streets in Palo Verde all ran from Effie Street to Park Row, with house numbers ranging from 1700 to about 1875. They were Bishop's Road, Davis Street, Curtis Street, Palo Verde Street (later renamed Paducah Street), Reposa Street, Gabriel Avenue, Malvina Avenue, and Boylston Street. A portion of Bishop's Road exists today in the parking lot of Dodger Stadium, and there still is a short block of Malvina Street alongside the parking lot of the Los Angeles Police Academy, whose address at one time was on Boylston Street. The address of the Elysian Park Recreation Center, now the Elysian Park Adaptive Center and where the Los Angeles Theater Academy (LATA) is located today had, at one time, a Bishop's Road address.

Streets in Bishop ran southwest from Effie Street, with house numbers below 1700. They were Davis Street, Paducah Street, Shoreland Drive, Home Place, Boylston Street, and Garibaldi Street. There is a short bit of Boylston Street that exists today; it is high on a loma, with a spectacular view of the fireworks displays that take place on certain Friday evenings following baseball games at Dodger Stadium. Before the evictions, the view would have been of the homes of their neighbors who lived with them in Bishop. There is also a very short portion of Shoreland Drive that exists today off of Boylston Street.

The following map is a 1948 aerial photograph, in which individual houses may be seen — hundreds of them, in all the communities. This photograph was taken just two years before the evictions began. The four communities are outlined as before, except that la Loma and Bishop are outlined in yellow for clarity.

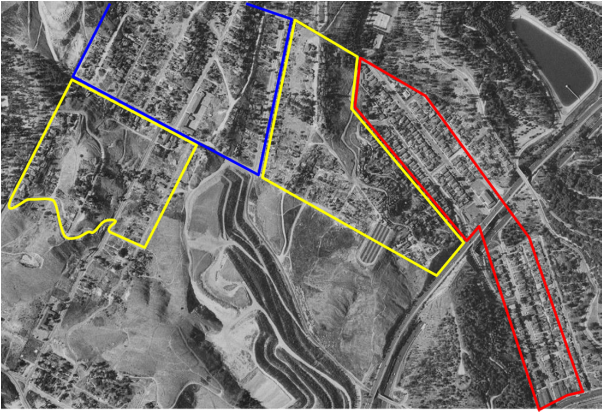

Finally, take a look at what is nearly the same aerial photograph, this one taken in 1952 — two years after the evictions began. There's not much that can be said about the destruction that had taken place in just two years, so see for yourself ...

While a few scattered houses remain in Chavez Ravine in this image, most of them in Palo Verde, the end had already been determined and was abundantly clear. Thus, less than seven years after this heart-rending photograph was taken, out of a well-developed, vigorous, and tightly-knit community of about 1,400 families, all of the houses in la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop — nearly 1,100 in number — had been leveled. Solano Canyon, which will celebrate its 150th anniversary in 2016, was the sole survivor.

This is the same area in 2015 ...

This is the same area in 2015 ...

Requiescat in pace, la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop.

Follow us!

What our friends are saying

"Thank you for such an informative site which highlights the plight of those relocated from Chavez Ravine. My stepfather was a happy child growing up in the Palo Verde area. He had many stories about living in the area and working at the [Ayala] store."

"Wow that is awesome thank you"

"Dodger Stadium will always be a monument to the displacement of three entire communities"