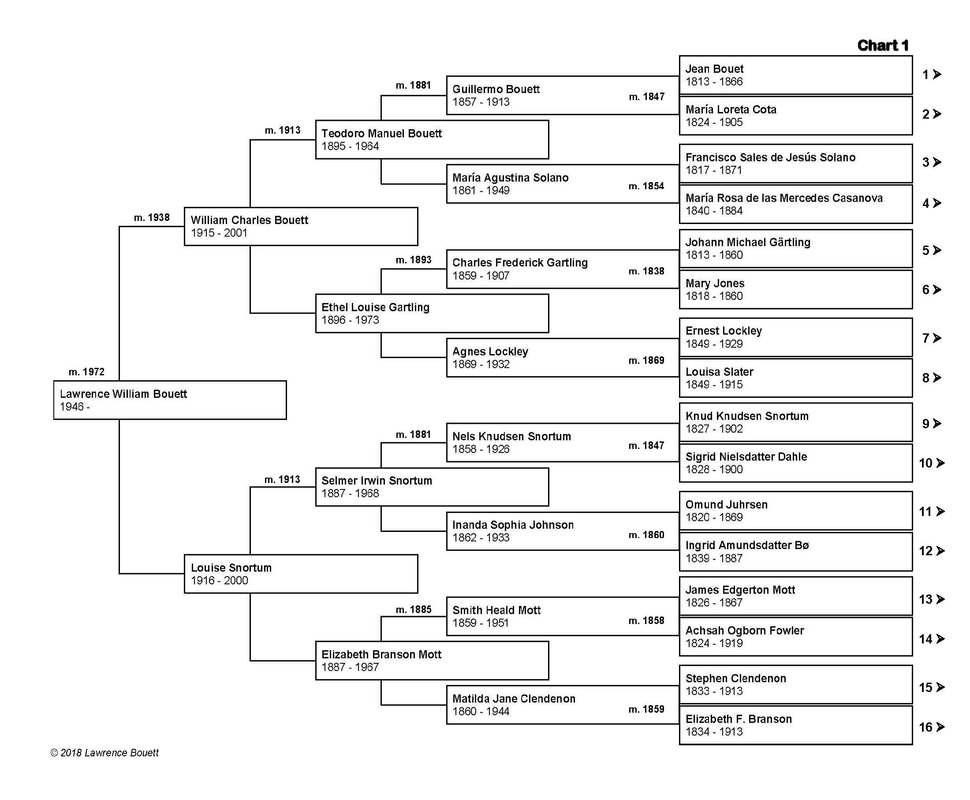

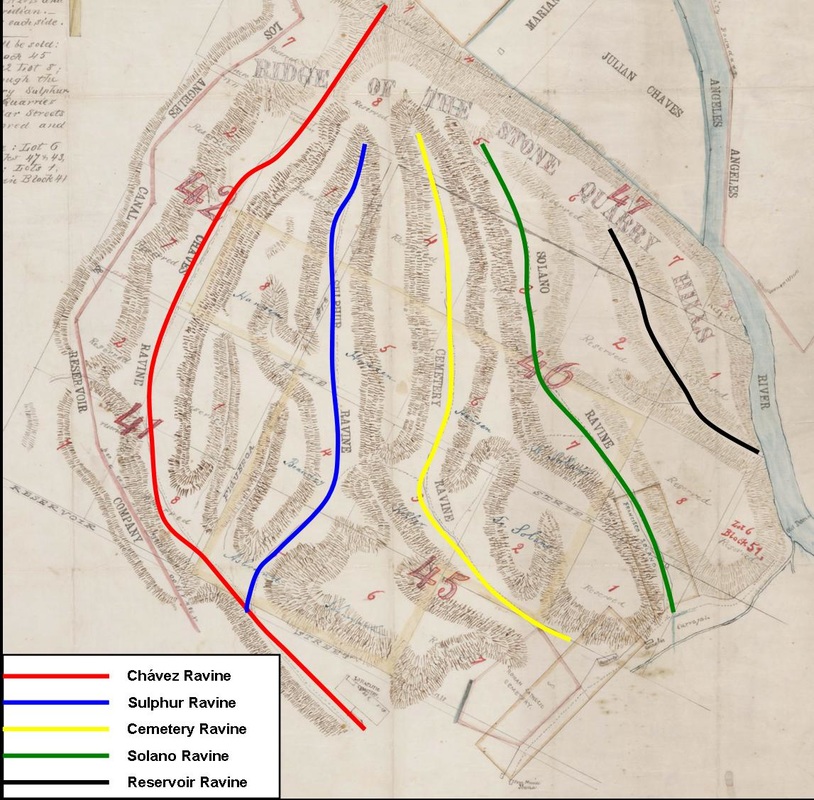

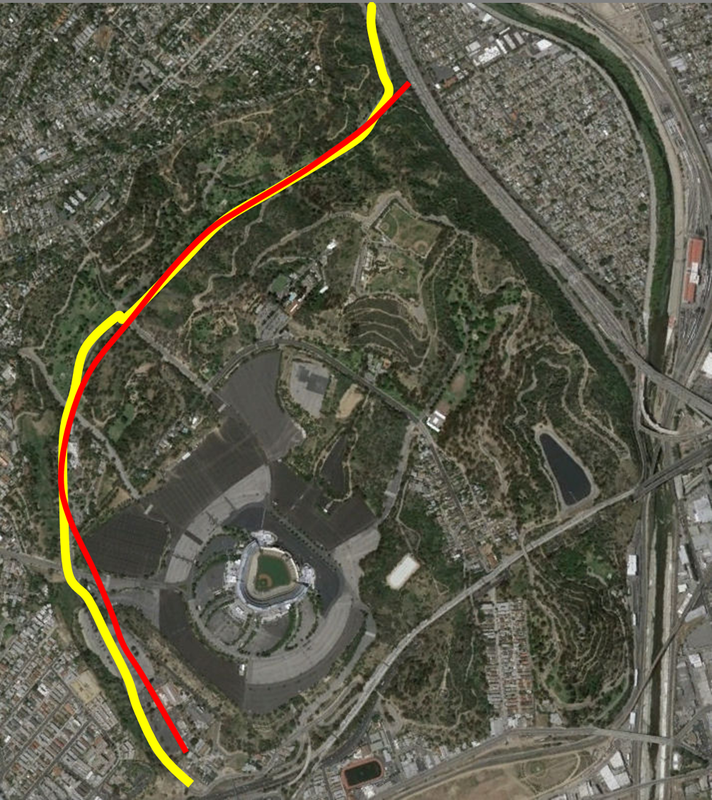

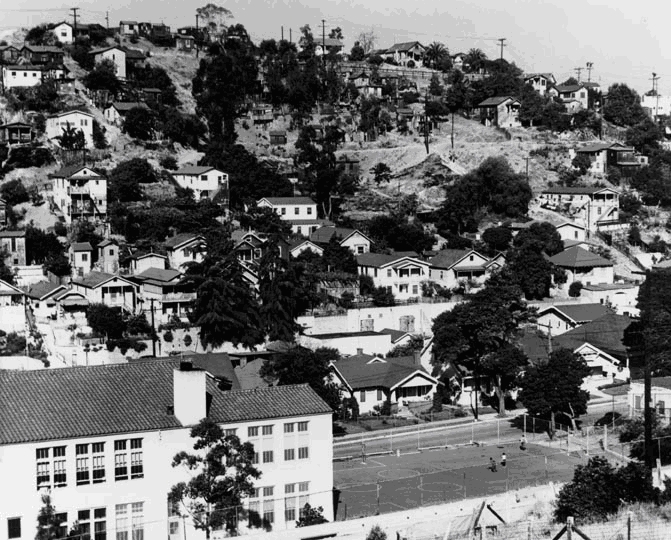

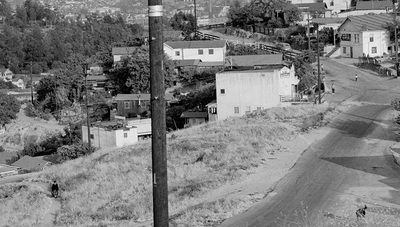

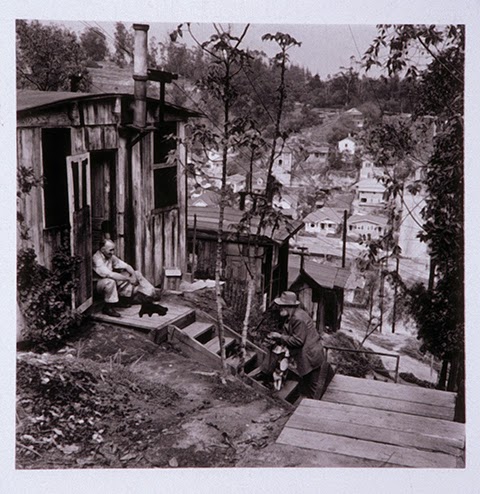

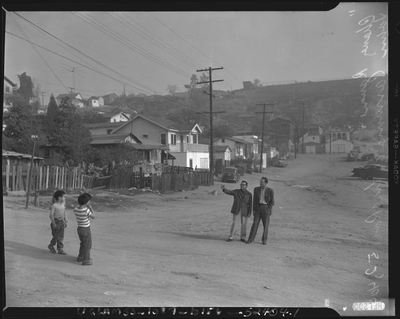

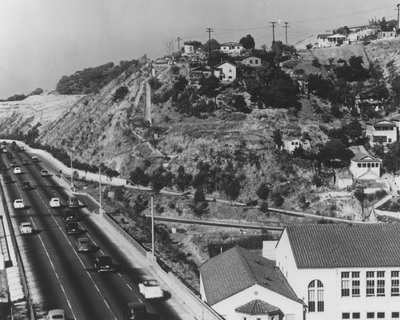

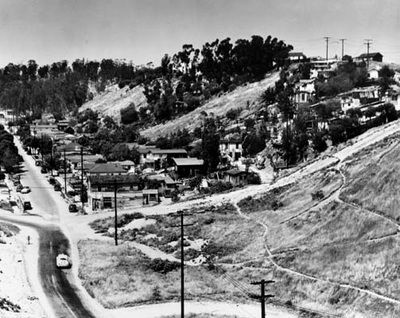

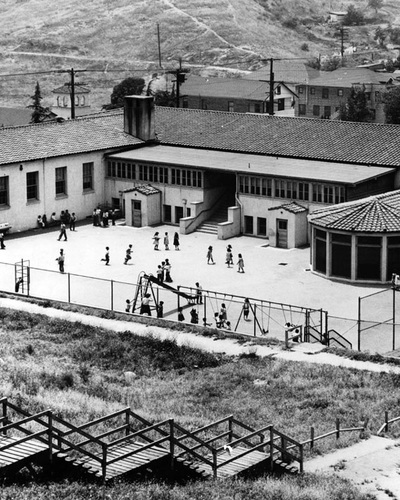

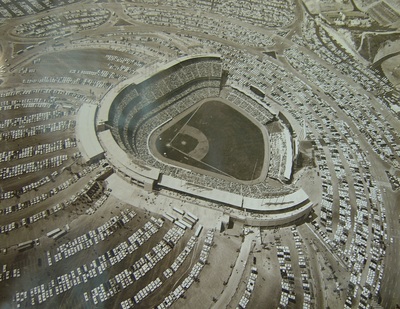

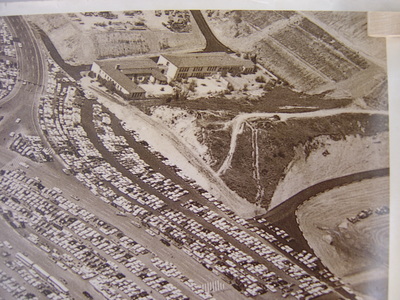

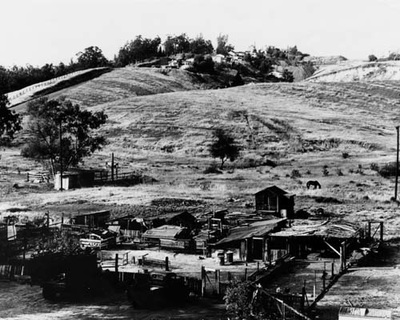

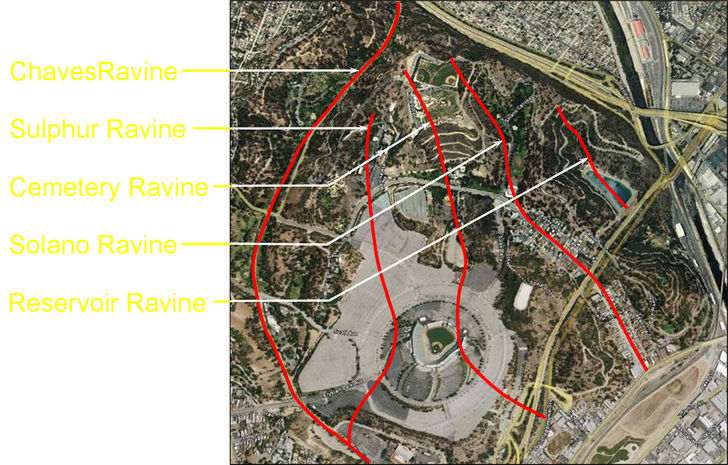

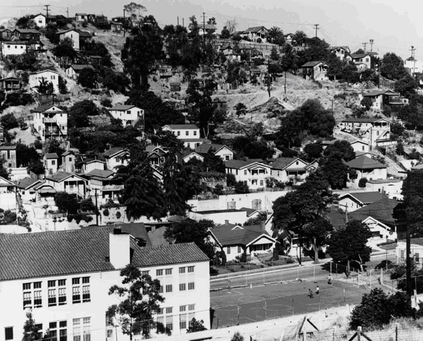

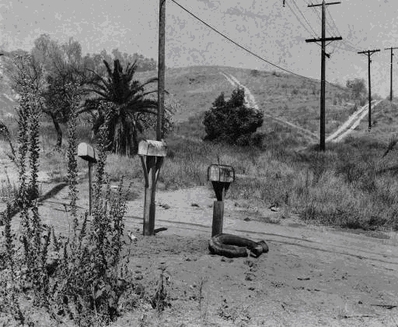

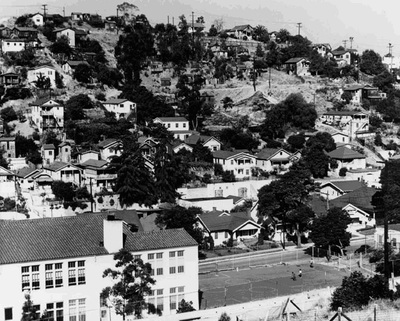

There is so much misinformation surrounding the term 'Chávez Ravine' that it becomes truly mind-boggling. First, of course, there is the ravine itself, which is a distinct geographical feature located far to the west of anything else that later bore its name. Next, there were the three so-called Chávez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, none of which was remotely connected to the actual Chávez Ravine. Finally, the name was ludicrously appropriated and mis-applied to Dodger Stadium, which was constructed against the bulk of a decimated Mt. Lookout, and which sits firmly astride Sulphur and Cemetery Ravines; again, with its having no connection whatever to the geographical feature called Chávez Ravine. This map, surveyed in 1868 by George Hansen and Wm. Moore, shows the Stone Quarry Hills as it looked at the time. This is a portion of the same map, but with the ravines identified. Reservoir Ravine was initially not named; it was named only after a reservoir was constructed at its mouth. Next, let's take a look at a modern image of the same area, with Chávez Ravine clearly marked; the red line is the original Chávez Ravine trail, and the heavy yellow line is the location of Stadium Way today. Finally, here's the same image, but with the approximate locations of the three so-called Chávez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop marked, along with historic Solano Canyon, which is outlined in red on the right-hand side of the image. By now, it should be clear that Chávez Ravine — the heavy red line on the left-hand side of the image — has nothing at all to do with either the communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop or Dodger Stadium. And, for that matter, if la Loma (the right-hand yellow polygon) is a part of Chávez Ravine—the Communities, then why not include Solano Canyon in that designation, too? In fact, la Loma was less a stand-alone community than it was a natural extension of Solano Canyon; it was simply the growth of population up and onto the loma that gave the community its name. To illustrate that argument, look at this 1930s-era photograph, taken from a point high above the Solano Avenue School, where most of the children from la Loma attended school, and looking up into la Loma. It is impossible to tell where Solano Canyon ends and la Loma begins. So what does it mean — if anything? It probably doesn't mean anything, in reality, other than to serve as a vestigal linguistic curiosity. But there does seem to exist a bit of a 'cult of Julián Chávez' surrounding the historical context of the names, and which, of course, is entirely unwarranted, given that the oft-repeated '83 acres' that Julián Chávez actually owned was not within Chávez Ravine itself, nor within any of the communities that co-opted his name, but rather on the northeast side of the Stone Quarry Hills, on the flat land by the Los Angeles River in the area that is known locally as Frogtown; and the Palo Verde Tract, which included all of la Loma, most of Palo Verde above Effie Street, and all of Bishop was subdivided and developed by Alfredo Solano, son of the founders of Solano Canyon, Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova, beginning in 1897.

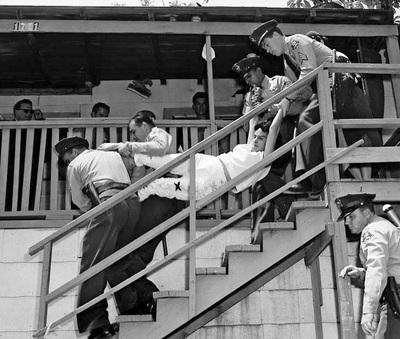

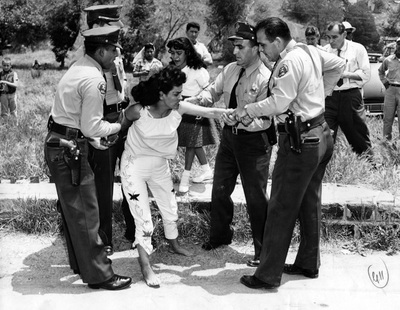

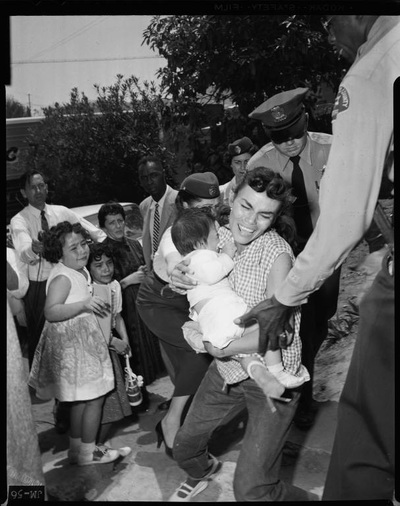

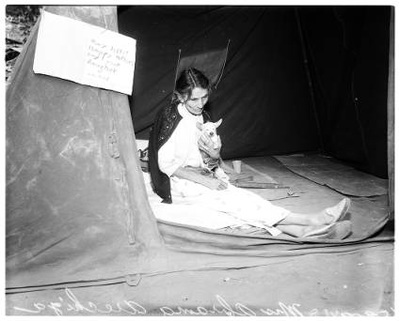

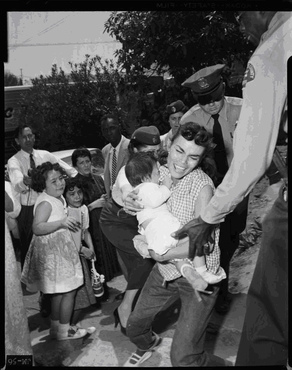

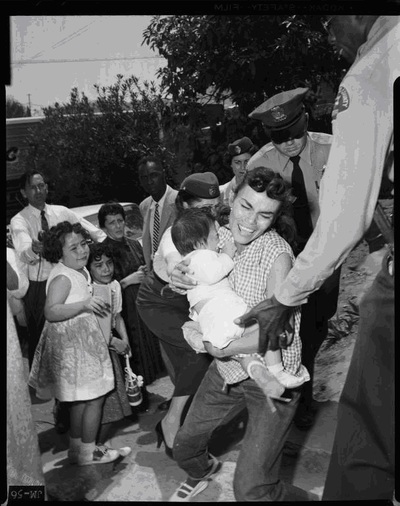

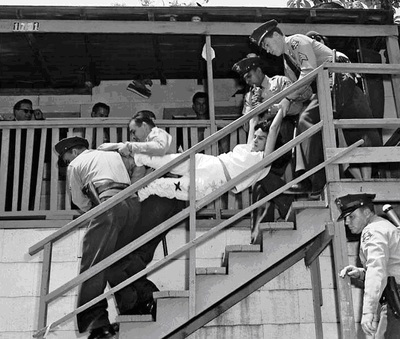

One further thing: it is entirely possible that the name Chávez Ravine derives not from Julián Chávez at all, but rather from his brother, Mariano, who once owned land high up in the ravine near the summit. And the Chávez Ravine trail itself led directly, not to the Frogtown properties of brothers Julián and Mariano Chávez, but to the adjacent, larger acreage of Juan Bouet, my great-great grandfather. The author was fortunate to have been able to attend, for the first time, the annual reunion and picnic of los Desterrados on Saturday, 18 July. For a historian and genealogist, it was a treasure chest of memories and living history. Although I am a relative outsider — I descend from the founders of Solano Canyon and no one in my family lived in Chávez Ravine — I felt welcomed, and I was able to talk with many of the residents and descendants of those who were displaced from la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop. Neither lightning nor rain (but no snow or sleet) ... Right at nine o'clock, as if on cue, the skies opened up, and a magnificent thunderstorm passed directly over the picnic site, accompanied by profuse lightning and heavy rain. Spirits were not dampened, however, and when it passed and the sun came out, it was a warm and pleasant day. The need to preserve history from living memory ... It is important to preserve and record the history that is within the memory of those who lived it. For something as momentous as the Chávez Ravine evictions, and for those of us who wish to study that event, it is particularly important. It is incredible how much the generation that went through the evictions — even as relatively young children — remember about the events of that time. ... by recording memories and asking questions That's the author on the left, asking a question to clarify a point from some of the ones who were actually there.

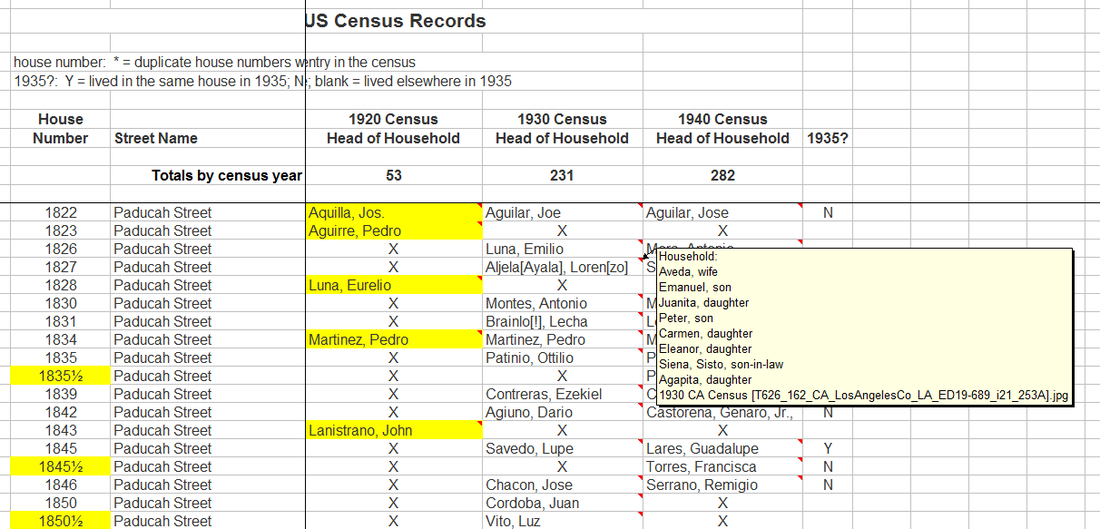

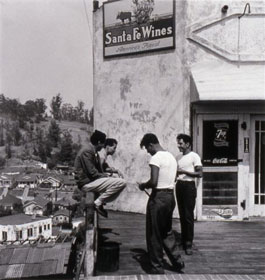

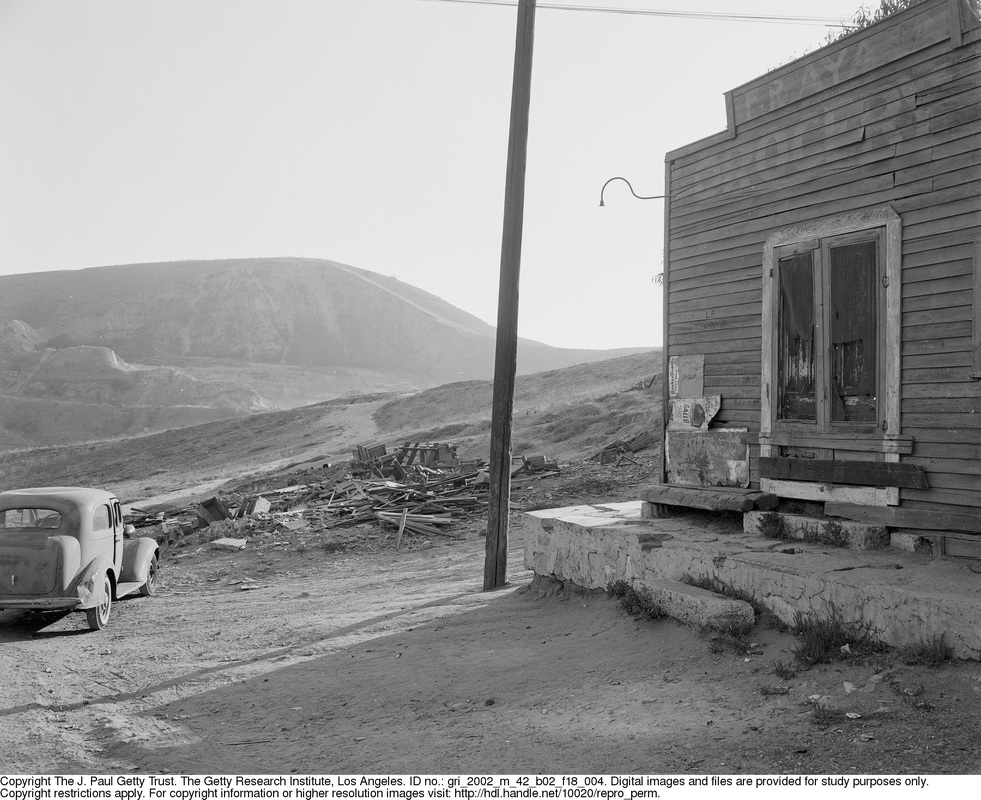

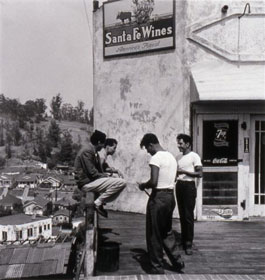

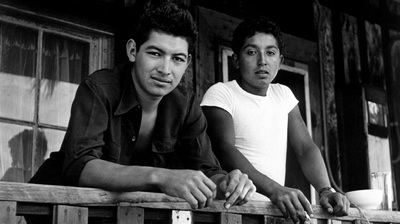

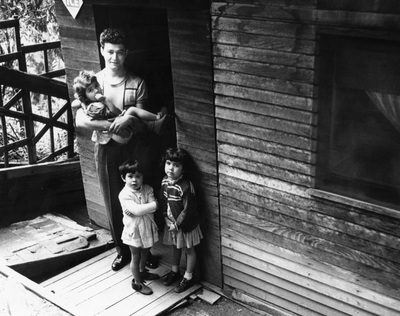

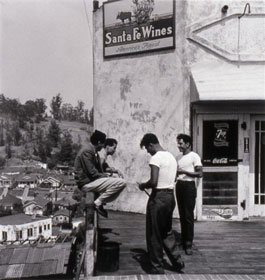

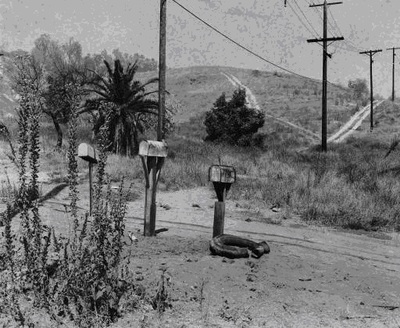

We at ChávezRavine.org want to take this opportunity to wish all of our readers a safe and happy Fourth of July celebration this weekend. If you've ever been confused — as I have — about the names and locations of the streets in the Chávez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, then you may appreciate this visual guide to the streets of la Loma. No matter where one lives, one must be able to shop for food to supplement that which is grown in one's garden, and to purchase those necessary household items that cannot be manufactured or grown in the garden. La Loma — the first of the Chávez Ravine communities — was no exception. There were many home gardens in la Loma, but there were also small stores, too This blog tells the story of the four known tienditas that served the community of la Loma. Every community must have places to shop There were, by the early 1920s, nearly two dozen families living in the emerging Chávez Ravine community of la Loma, that represented more than 100 people. During the early years of the 1920s, not one, not two, but three grocery stores were opened, plus a fourth that served both la Loma and its elder sibling, the neighboring community of Solano Canyon, and which is still in existence, although it is currently closed. Stores were typically run out of someone's house; additional rooms were added as they were needed for family living space as the size of the family expanded. Interestingly, ownership of these home-grown, family businesses tended to remain in the hands of the founding families for many years. The first store: Mazzarini's The first store to serve the growing community of la Loma may actually have been in Solano Canyon. On April 19, 1922, Valentino Mazzarini applied for a permit to build a 24' x 48' x 15', four-room "dwelling and store" at 728 Amador Street. Cost was estimated at $2,000 ($28,300 today). At the time, Mazzarini lived at 626½ New High Street in Los Angeles, and he named himself as the contractor. Mazzarini, a 49-year-old Italian from Ferrara who immigrated to the United States in 1914 along with his wife, Irinia, had a 9-year-old son, George. Mazzarini's store must have been an immediate success, because just 16 months later, in August of the next year, 1923, he built a 10' x 30', two-story house on the property, followed in October, 1924 by an addition to the store, at which time he stated that there were not one, but two residences on the site in addition to the store. The family of Valentino Mazzarini is found in the 1930 and 1940 censuses, living at 728 Amador Street, the location of their store. Valentino Mazzarini died in 1955 and is buried at Forest Lawn in Glendale along with his wife, Iniria, who died in 1942. Sometime between the death of Valentino Mazzarini in 1955 and 1966, Lindow Seu became the owner of the store that Mazzarini built. By then, there were three residences on the property plus the store. About 1968, Lindow Seu sold the property to "Big John" and Tillie Agnick, and the store became known as John's Market. Question: Do you know the identity of the person who is standing on the steps of John's Store? (The answer is below.) At some point, John and Tillie turned over day-to-day running of the store to a couple named Conrad and Betty, who ran the store for many years until it closed about 1980. There is hope in the community today that the store will be opened again one day. John's Store was 'the place' for neighborhood kids to hang out. The kids were mostly skaters — roller-skaters, that is — and the big attraction were the three arcade games inside the store: Asteroids, Galaga, and Frogger. The store was so small that there was room inside for one player but no spectators, so the other kids had to wait their turns outside, after having put down their quarters to reserve their place in line. It was the era of AbbaZabbas, Butterfingers, Fun Dip candy, and 25¢ pickles. Conrad and Betty always let the kids to hang out at the store; they were allowed "... just to be kids ...", in the words of one habitué. Answer to the question, above: This is Bobby Romero, brother of Betty, who ran the store with her husband, Conrad. Gennaro's liquor store and Elysian Grocery Still during the 1920, but shortly after Valentino Mazzarini opened his store in Solano Canyon, Serafín Castillo opened a store at 1860 Brooks Avenue in la Loma. This was probably the first store actually to open in la Loma itself. Castillo may actually have owned two stores: Gennaro's and Elysian Grocery. The two buildings were back-to-back, as seen in this cropped photograph from 1950 (photograph, below left). The middle photograph was taken in 1925 inside Elysian Grocery; the man in the center is the owner, Serafín Castillo. The right-hand photograph shows some locals 'hanging out' at Gennaro's. The large building to the right of the telephone pole in the left-hand photograph, above, is Gennaro's, located at 1760 Brooks Avenue. The smaller building just to the left of the pole and lower in elevation is Elysian Grocery, which appears to be located on Phoenix Street. Since Serafín Castillo owned Elysian Grocery and his 1940 census address was 1760 Brooks Avenue, and since Gennaro's was located at 1760 Brooks, it is reasonable to conclude that Castillo was the owner of both businesses. The man on the left in the middle photograph is identified as Aurelio Domínguez; the third man (right) is not identified. Serafín H Castillo earned his American citizenship in 1942. The right-hand image was taken by Don Normark in 1949 outside Gennaro's. It was published in Normark's book, Chávez Ravine, 1949: A Los Angeles Story. The young men who are enjoying a relaxing afternoon are identified (from left to right) as Tony Rosales, John Vasquez, Carlitos, and Murphy Hernandez. They referred to the business Jerry's liquor store. Florencio R. Ayala's Grocery A fourth grocery store was recently discovered that also served la Loma: that of Florencio R. Ayala, and which was located at 853 Effie Street, on the corner of Effie and Spruce Streets. This location is on the southern, downhill side of the loma, between Pine Street and Brooks Avenue. Florencio R. Ayala was born in México about 1886. He came to the United States about 1905 and married his wife, Martina, in the U.S. in 1932. In 1930, their adopted daughter, Lupe, was living with them, and in 1940, they had a son, Martín, and a daughter, Florencia, in the household. Florencio Ayala applied for a permit to build an addition to an existing house in June, 1924, so the house — and probably the store — was in existence before that date. This photograph was taken by Lenard Nadel about 1952, after the destruction; the building is clearly no longer occupied, and it, like everything else in la Loma, was eventually destroyed. So who came first? Whether Mazzarini's store in Solano Canyon was the first to open is itself an open question. The truth is that it doesn't really matter, since all of the four stores that served the la Loma community were open during the early-to-mid 1920s. They were built and run by enterprising immigrants who were determined to make a life for themselves in the coolness of the Stone Quarry Hills. None of them except Mazzarini's survived the destruction of the 1950s, however; there isn't a trace of Gennaro's, Elysian Grocery, or A. R. Ayala Grocery left today. What did we miss?If anyone can contribute information or an anecdote about any of the stores described here, we welcome your comments. Use the Contact Us link at the top of the blog or use the direct e-mail link to the author in the sidebar to the right.

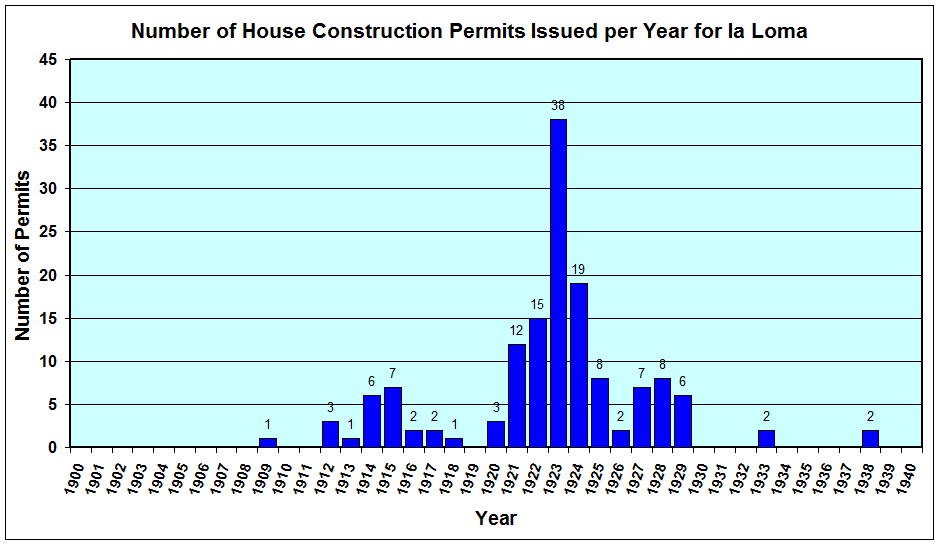

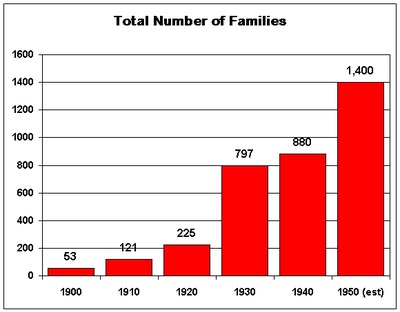

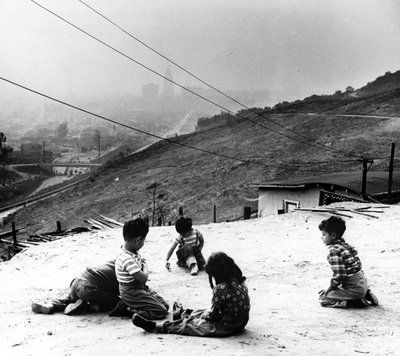

This is the first of three blogs whose purpose is to tell the stories of the Chávez Ravine communities that were destroyed to make way for what ultimately became Dodger Stadium. This blog is dedicated to la Loma, the first Chávez Ravine community to arise, beginning in 1909.

|

About the AuthorLawrence

Bouett is a retired research scientist and registered professional

engineer who now conducts historical and genealogical research

full-time. A ninth-generation Californian, he is particularly interested in the displacement of the nearly 1,100 families that lived in the Chavez Ravine communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop to make way, ultimately, for the construction of Dodger Stadium. His ancestors arrived in California with Portolá in 1769 and came to Los Angeles with the founders on September 4, 1781. CategoriesArchives

January 2018

|

Follow us!

What our friends are saying

"Thank you for such an informative site which highlights the plight of those relocated from Chavez Ravine. My stepfather was a happy child growing up in the Palo Verde area. He had many stories about living in the area and working at the [Ayala] store."

"Wow that is awesome thank you"

"Dodger Stadium will always be a monument to the displacement of three entire communities"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed